The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated several lockdowns across the world to control the spread of the virus. After December 2020, Ireland went into a second COVID-19 lockdown. In May 2021, the advanced midwife practitioner service in a northwest Ireland maternity unit noticed a cluster of 12 emergency caesarean section births in a 6-week period and 31 vaginal births with all babies weighing over 4kg. The advanced midwife practitioner also noted that the majority of the 43 women in this group visually appeared to have increased their body mass index compared to that calculated at booking. The majority felt they had gained a lot of weight, with some knowing their current weight, verifying the observation.

When asked, almost all the women reported eating more, exercising less and gaining weight during pregnancy. Weight gain had been discussed at the first encounter with the advanced midwife practitioner. All women were advised that a weight gain of around 15kg was normal, with a gain of >20kg potentially increasing their risk of a caesarean section birth, raised blood pressure or a large for gestational age baby (Khanolkar et al, 2020). There was also a discussion signposting women to healthy eating in pregnancy, as per healthy Ireland and the my pregnancy book (Health Service Executive (HSE), 2018a), which every woman receives at the booking-in visit.

The women had also been advised not to eat for two but to eat healthily for one. At the time, women were only weighed at the booking-in appointment, there was no routine monitoring of weight gain for the rest of the pregnancy (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2010). However, if the advanced midwife practitioner felt a woman had gained excess weight, women were weighed and monitored through the rest of the pregnancy, with health promotion and healthy eating discussed based on individual needs (HSE, 2016; 2018b, Tommy's Pregnancy Hub, 2021).

Following the advanced midwife practitioner noting the rise in birth weight and caesarean section rate, she reflected on her previous clinical experience in Scotland. In the 1990s, prior to the phasing out of routine weighing in pregnancy and the rise in obesity in the population, women were weighed at each antenatal appointment and babies weighed on average 3–3.5kg (Allen-Walker et al, 2020). However, the advanced midwife practitioner noted that babies currently weigh closer to 4kg or more, increasing from when routine weighing was stopped.

A literature search was undertaken by the advanced midwife practitioner to discover if research could verify this observation. The studies found reported that monitoring weight in pregnancy was used to detect pre-eclampsia and low birth weight babies but was proven not to be effective in the 1990s (Fealy et al, 2020). Routine weighing was stopped based on research findings that restricting weight gain did not improve perinatal outcomes (NICE, 2010), but resulted in undue anxiety in pregnant women (Allen-Walker et al, 2020). There was also insufficient evidence to support the recommended weight gain (Table 1) identified by the Institute of Medicines (IOM) (Fealy et al, 2020). NICE (2010) advise calculating body mass index at booking, and for those with a body mass index of over 30 to use the opportunity to discuss eating habits, physical activity and refer to a dietitian. Ongoing American-based research has demonstrated a link between excessive weight gain and gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, caesarean birth and large for gestational age babies (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2013; Khanolkar et al, 2020). Follow-up studies have confirmed these findings, but also identified a correlation between excess weight gain in pregnancy and ongoing postnatal obesity and weight retention, diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease (Allen-Walker et al, 2020; Mardones et al, 2021; Tam and He, 2021; Thruong et al, 2021). Excessive pregnancy weight gain also increases fat stores in the baby and is linked to childhood obesity and hypertension (Mardones et al, 2021; Tam and He, 2021; Thruong et al, 2021).

Table 1. Weight gain in pregnancy guidelines

| Category (body mass index) | Recommended total gain (kg) |

|---|---|

| Underweight (<18.5) | 12.5–18.0 |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 11.5–16.0 |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 7.0–11.5 |

| Obese (≥30.0) | 5.0–9.0 |

Based on the link between excess weight gain, hypertension, caesarean birth and an obesity rate of 16% worldwide in 2016 (Aung et al, 2021), the advanced midwife practitioner decided to be proactive regarding monitoring weight in pregnancy. A medical grade weighing scale was purchased and routine weighing of all women attending the service commenced in June 2021. The IOM recommended weight gain (Table 1) was discussed and women were signposted to resources for healthy eating and exercise in pregnancy (HSE, 2018b, c; Tommy's Pregnancy Hub, 2021).

Aims and objectives

This intervention was conducted to ascertain if monitoring weight gain in pregnancy ensures that women maintain a healthy weight, optimising maternal and neonatal outcomes. Body mass index is calculated and documented at the booking-in clinic for all women (NICE, 2010), and pregnancy weight gain was assessed as per the 2009 IOM guidelines (Table 1) (Khanolkar et al, 2020).

The study aimed to determine if maternal weight gain above IOM recommendations resulted in hypertension or pre-eclampsia, caesarean section, birth weight >4kg or neonatal intensive care unit admission.

Methods

The pre-intervention group (no routine weighing) included all women who attended the advanced midwife practitioner service for all antenatal care and gave birth in a particular maternity unit in northwest Ireland between 1 April and 31 May 2021 (n=58). The post-intervention group (routine weighing) included all women attending the service who gave birth between 1 October and 30 November 2021 (n=46). A retrospective review of all maternity records was undertaken.

Data collection

Data were collected by two student midwives, overseen by the advanced midwife practitioner. All women attending the service who gave birth during the stated timeframe were included. The pregnancy record was obtained and data collected using an amended pre-existing audit questionnaire to capture the information required to compare and report findings and outcomes in the pre- and post-intervention groups. These data were parity, age, body mass index, booking weight, weight at birth, total weight gain, type of birth (spontaneous vaginal birth, ventouse, forceps, elective caesarean section or emergency caesarean section), baby's weight and any adverse outcomes (excess weight, blood pressure, pre-eclampsia, caesarean section, neonatal intensive care unit admission).

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed and written up in conjunction with the local clinical audit support team in December 2021. The data were cross-checked by the team and reported as frequencies and percentages.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the study was not required according to the local research and education committee. There were no interventions or manipulation of participants. To comply with local guidelines when undertaking clinical audits in the hospital, a clinical audit proposal form was completed and submitted to the local clinical audit support team prior to commencing the study.

Results

Standards compliance

Two standards were assessed for compliance in the reviewed maternity records. The first standard was that body mass index was calculated and documented at the booking-in clinic for all women, which was completed in 100% of reviewed records. Body mass index is routinely calculated for all women at the booking-in appointment, and those with an index of over 30 are scheduled for a glucose tolerance test at 24–28 weeks. The second standard was that pregnancy weight gain was assessed as per IOM guidelines. Overall, 30% of women were within the recommended weight gain for their body mass index.

Comparison of pre- and post-intervention groups' obstetric characteristics

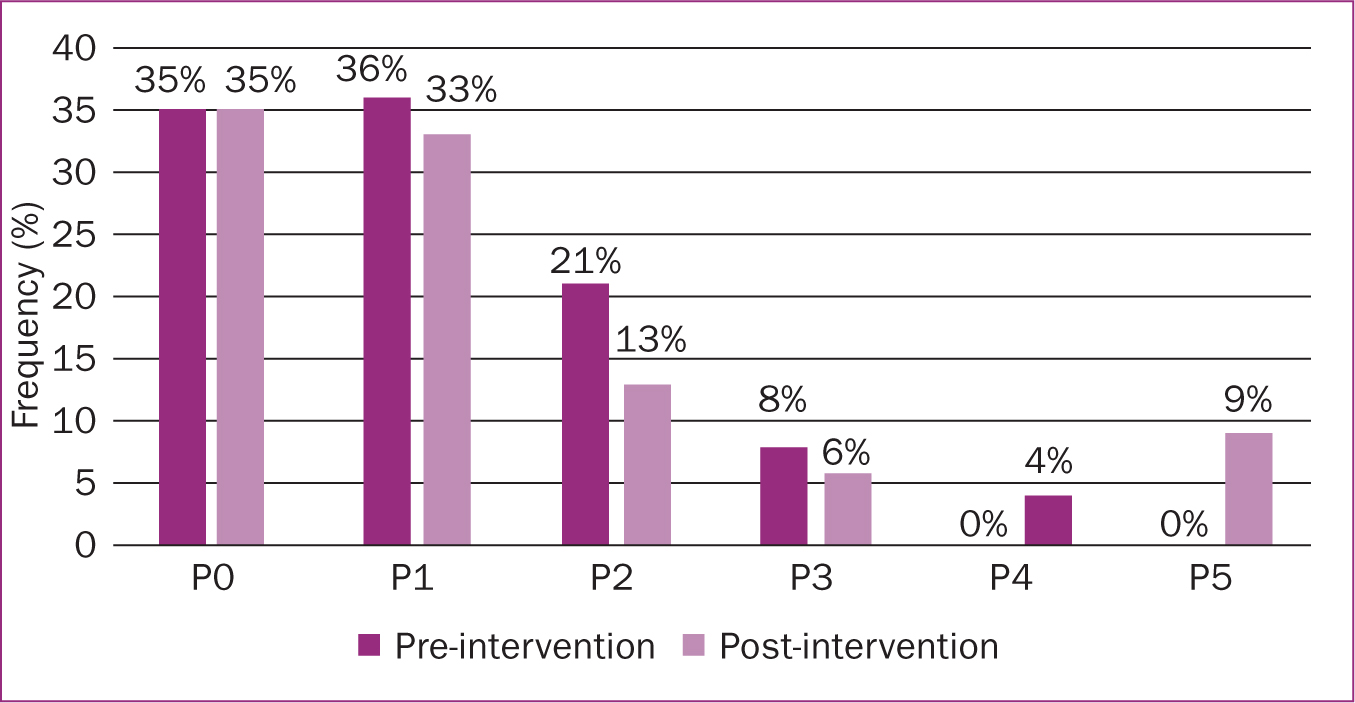

The demographics for parity (Figure 1), gestation at birth (Figure 2) and booking body mass index (Figure 3) were similar in the pre- and post-intervention groups, though this was not statistically tested. For the pre-intervention group, the most common parity was para 1 (36%), followed closely by para 0 (35%). For the post-intervention group, the most common parity was para 0 (35%).

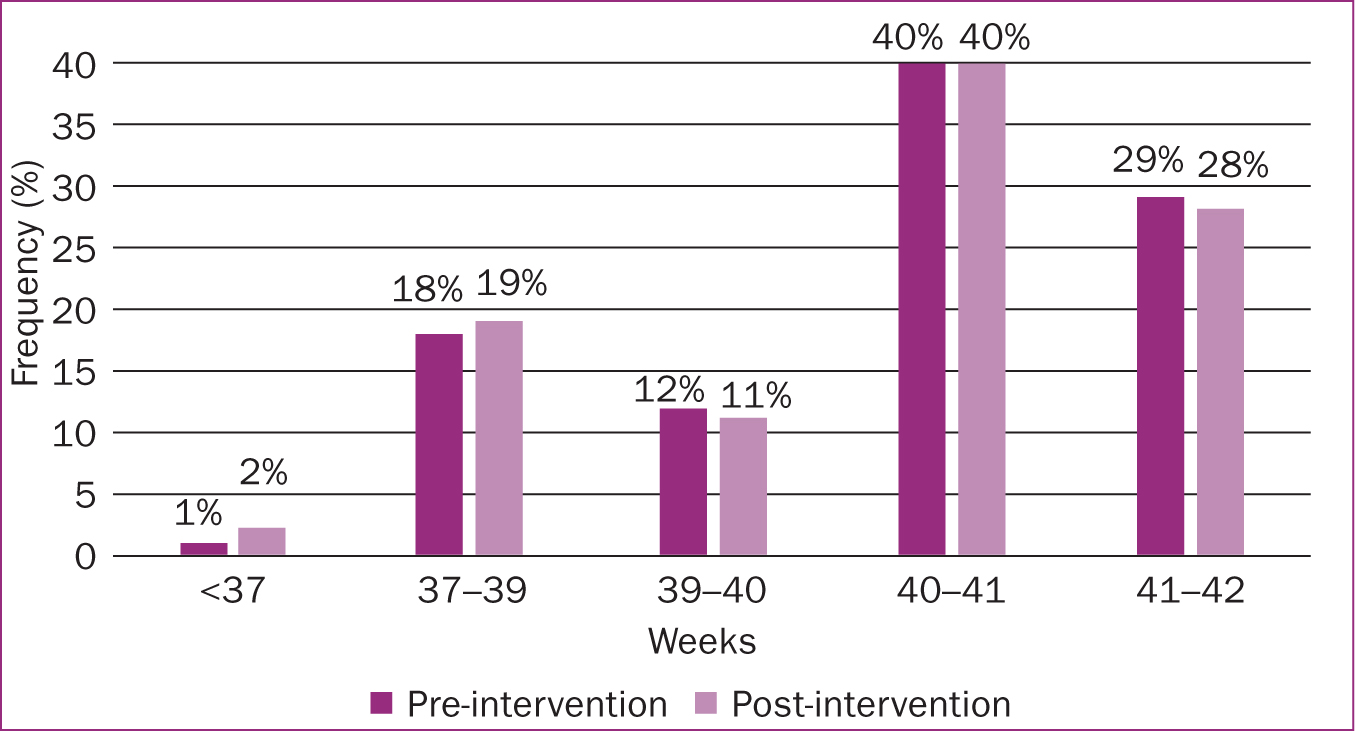

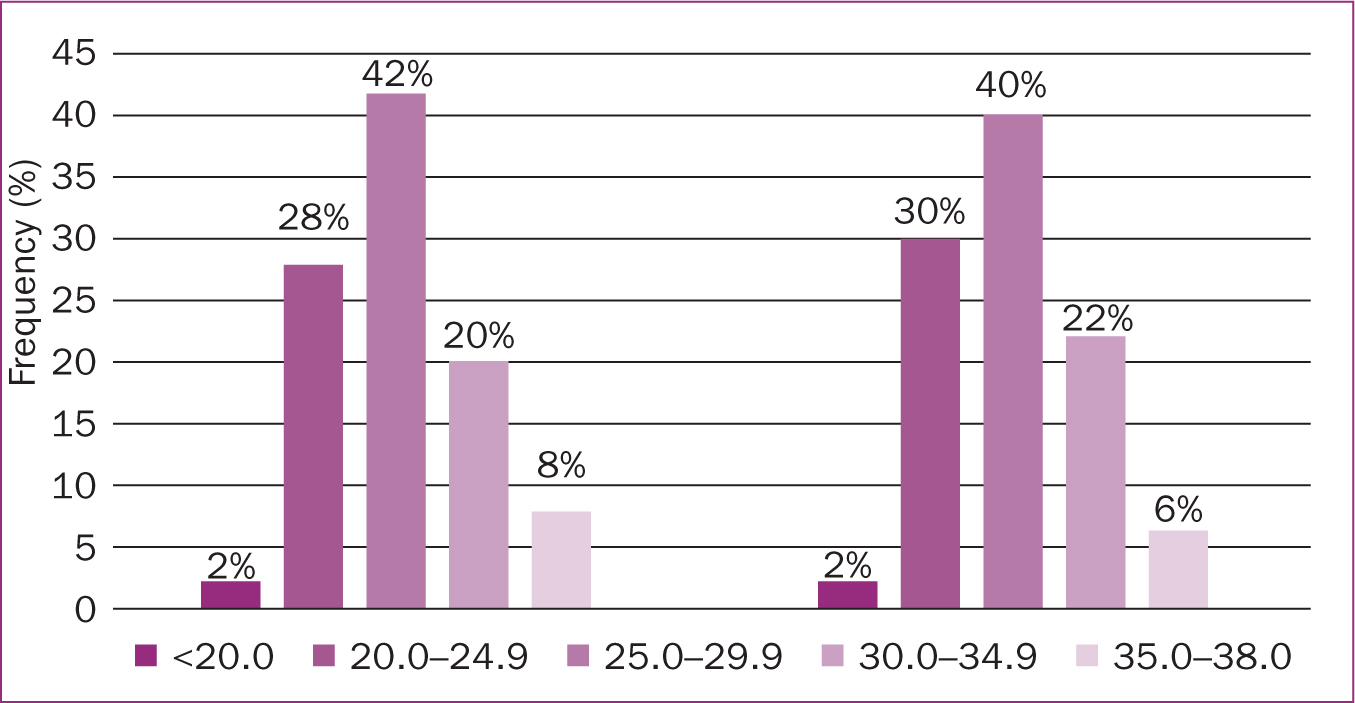

The most common gestation at birth in both groups was 40–41 weeks (40% for both groups), and the most common body mass index at booking was 25–29.9 (42% pre-intervention group, 40% post-intervention group).

Booking body mass index

In both groups, the majority of women had a booking body mass index of over 25 (Figure 3): 70% in the pre-intervention group and 68% in the post intervention group. In both groups, only 2% of women had a body mass index of less than 20.

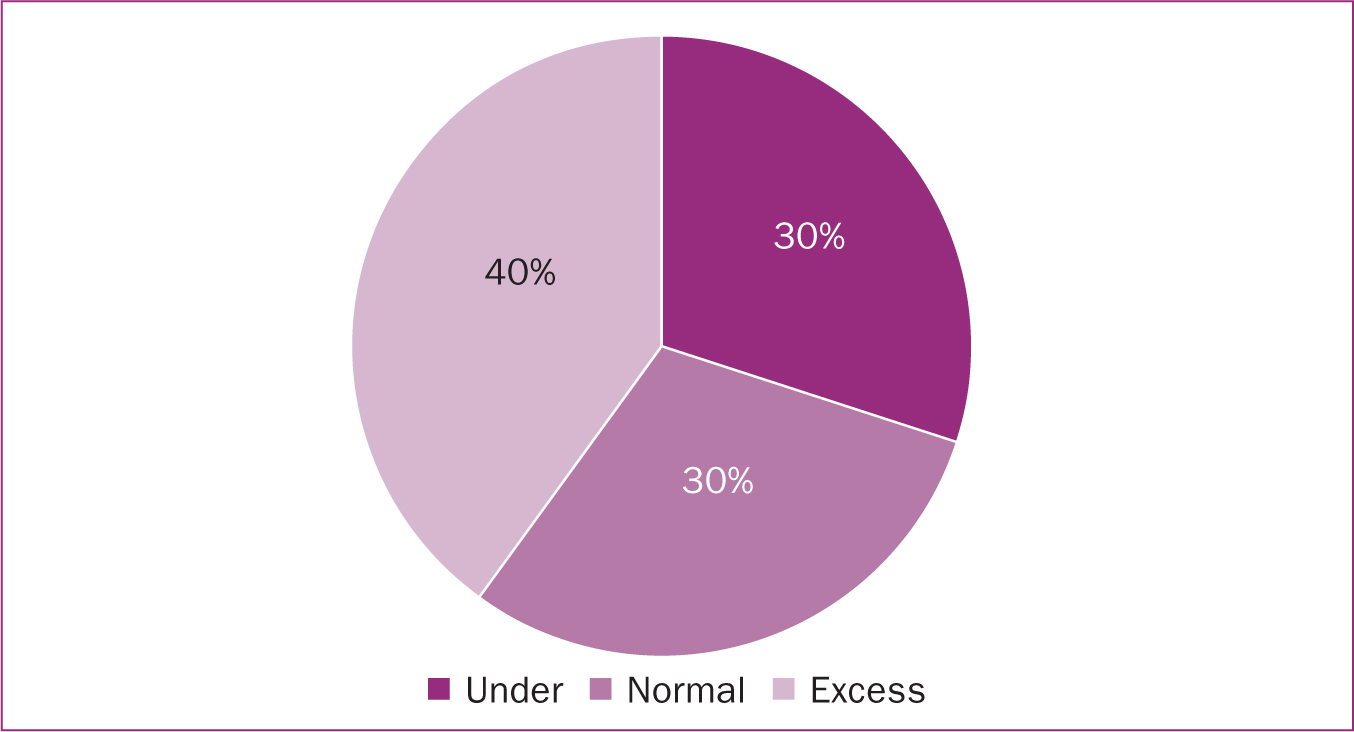

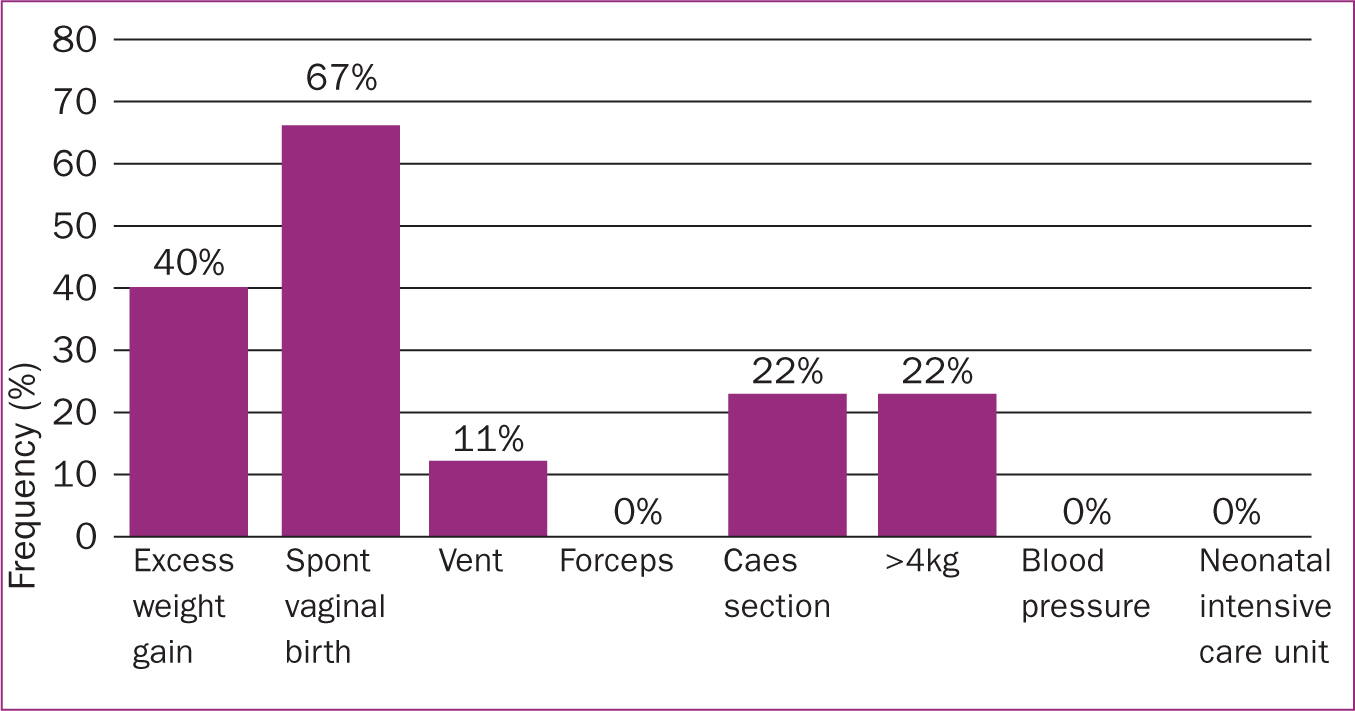

Pregnancy weight gain

In the pre-intervention group, 23% of women gained over 15kg during pregnancy with 4% gaining over 20kg. No participant gained over 30kg. If the IOM recommendations for weight gain had been applied to the pre-intervention group, 52% would have been categorised as having excessive weight gain. In the post-intervention group, when weight gain was based on IOM recommendations, 40% of women had excessive weight gain. In total across both groups, around a third (30%) of women gained less than recommendations while 30% had normal pregnancy weight gain and 40% had excess weight gain (Figure 4).

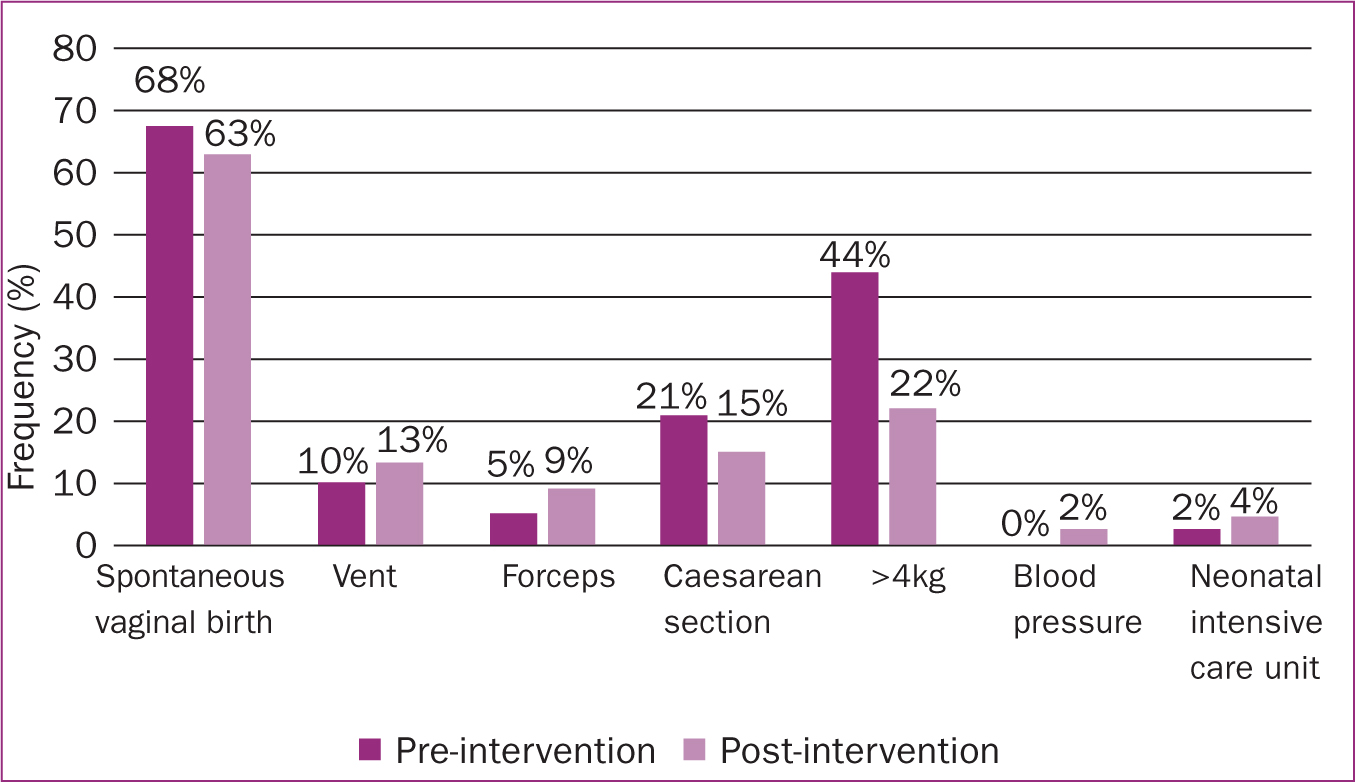

Raised blood pressure

In the pre-intervention group, none of the women had raised blood pressure. In the post-intervention group, 2% of women had raised blood pressure (Figure 5), but had a normal weight gain in pregnancy based on the IOM recommendations. Half of these participants had had raised blood pressure in their previous pregnancy. According to the IOM recommendations, none of the women who gained excess weight had raised blood pressure (Figure 6).

Caesarean section birth

In the pre-intervention group, there was a 21% (n=12) overall caesarean section birth rate, with a 15% rate in the post-intervention group (Figure 5). In the post-intervention group, 15% of women had a caesarean section birth (Figure 5). Based on the IOM recommendations, 22% of women with excess weight gain had a caesarean section birth (Figure 6).

Neonatal intensive care unit admission

In the pre-intervention group, 2% of babies were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (Figure 5), all of whom were born to women who had gained excess weight during their pregnancy. In the post-intervention group, 4% of babies were admitted (Figure 5). Their mothers had normal or low weight gain during pregnancy and 50% were admitted for low blood gases at the time of their emergency caesarean section birth, with fetal distress being the reason for the caesarean section. The remaining 50% were admitted with suspected sepsis based on maternal pyrexia in labour. Based on the IOM recommendations, in the post-intervention group, no babies were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit whose mothers had excess weight gain in pregnancy (Figure 6).

Birth weight

In the pre-intervention group, 44% of babies were born weighing over 4kg (Figure 5). The majority (80%) of the women giving birth to these babies had gained excess weight according to IOM guidelines, with 20% having had normal weight gain. In the post-intervention group, 22% of babies were born weighing 4kg or more (Figure 5). No baby in either group was born weighing over 5kg. Based on the IOM recommendations, 22% of babies weighing over 4kg were born to women in the post-intervention group who had gained excess weight (Figure 6).

Discussion

There is no worldwide consensus on routine monitoring of maternal weight gain in pregnancy and whether it should be used as a screening tool to detect maternal or neonatal adverse outcomes (Fealy et al, 2020). The IOM continues to report adverse outcomes related to insufficient or excess weight gain in pregnancy, including gestational diabetes, caesarean section birth, small and large for gestational age and preterm birth (Fealy et al, 2020). Pregnancy weight gain is a recognised predictor for fetal growth, but there is no agreement on guidelines for normal weight gain in pregnancy, with only the IOM identifying this in their 2009 clinical guideline (Fealy et al, 2020).

In 2021, Ireland was reported to have one of the highest obesity rates in Europe, with 60% of adults having a body mass index over 25 (HSE, 2022).The present study assessed the effectiveness of an intervention for improving healthy weight gain during pregnancy, through regular monitoring according to IOM standards at an advanced midwife practitioner service in Ireland. The study examined the impact of regularly monitoring weight gain during pregnancy on birth outcomes, including mode of birth, incidence of hypertension and pre-eclampsia and babies born small or large for gestational age. Ensuring pregnancy weight gain followed IOM recommendations was a new initiative for advanced midwife practitioner service users, and so compliance was lower than expected. However, this will be part of ongoing quality improvement in the service, with a reaudit scheduled for the fourth quarter of 2022.

For both the pre- and post-intervention groups in this study, the majority of women had a booking body mass index of over 25. Based on a study by Tam and He (2021), women who are overweight or obese at their booking in appointment are more likely to gain weight in excess of IOM recommendations during their pregnancy. This then predisposes them to postnatal weight retention with ongoing obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension (Tam and He, 2021). Across both groups, 40% of women gained excess weight during their pregnancy (Table 2), in-keeping with the 36.6% excess gain reported by Rogozinska et al (2019) in their review of 36 randomised trials across 16 countries. This study included 4429 women and showed that two-thirds of women had wight gain in line with the IOM recommendations, with 36.6% gaining excess weight having increased likelihood of caesarean section birth and large for gestational age babies (Rogozinska et al, 2019).

Table 2. Review findings vs international findings in excess of Institute of Medicine recommendations

| Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Present findings | International findings | |

| Excess weight gain | 40.0 | 36.6 |

| Hypertension or pre-eclampsia toxaemia | 0.0 | 10.0 |

| Caesarean section birth | 22.0 | 37.6 |

| Weight>4kg | 22.0 | 3.0 |

| Neonatal intensive care unit | 0.0 | 5.0 |

The present study reported a 0% rate of hypertension/pre-eclampsia in both the pre- and post-intervention groups, compared to a 10% rate reported in international research (Thruong et al, 2021) (Table 2). Thruong et al (2021) also reported that 37.6% of women with excess weight gain gave birth by caesarean section, compared to 22% of women in the present study (Table 2). Turienzo et al (2021) described how continuity of care giver results in a trusting relationship. The woman feels safe, secure and respected, with easier access to engage with the healthcare professional for problem solving or early diagnosis (Turienzo et al, 2021). The women attending the advanced midwife practitioner service had access to the service Monday to Friday via telephone or email and received continuity of carer throughout the pregnancy, which may account for lower pregnancy-induced hypertension. This finding may not be replicated when reaudited.

The caesarean section rate was 21% in the pre-intervention group, lowered to 15% in the post-intervention group; for women who gained excess weight in the post-intervention group, the rate of caesarean section was 22%. A caesarean birth is more likely for women of all body mass index categories when there is excess weight gain in pregnancy (Rogozinska et al, 2019).

In the pre-intervention group, 44% of babies were born weighing over 4kg, whereas in the post-intervention group, 22% of babies weighed over 4kg. This is greater than reported in international research, which cites a 3% rate of large for gestational age babies in women who gain excess weight in pregnancy (Thruong et al, 2021). Thruong et al's (2021) USA-based retrospective study of over 2 million normal risk, singleton term births reported maternal and neonatal outcomes over a 2-year period based on excess pregnancy weight gain. There was a sixfold increase in large for gestational age babies but only reported numbers for babies over the 97th percentile at birth (Thruong et al, 2021). In the maternity unit where the present study was undertaken, birth percentiles are not calculated, which may account for the difference in findings. Including figures for large for gestational age babies will form part of the next audit. All babies born weighing over 4kg in the post-intervention group were born to women who gained excess weight according to the IOM recommendations. Rogozinska et al (2019) reported that the likelihood of having a large for gestational age baby is increased for women of all body mass index categories where there is excess weight gain in pregnancy.

In the pre-intervention group, 2% of babies born to women with excess weight gain were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit, while no babies born to women with excess weight gain in the post-intervention group were admitted. This was less than found by Thruong et al (2021), who cited a 5% neonatal intensive care unit admission rate for excess weight gain in pregnancy (Table 2). The present study's advanced midwifery practice service had a neonatal intensive care admission of 5%, with the local maternity unit having a neonatal intensive care admission rate of 11% (Saolta, 2021). This lower rate of admissions is supported by the secondary outcome findings of midwifery-led continuity of care, as described by Sandall et al (2016).

Australia reintroduced routine antenatal weight monitoring in 2018 as a simple health promotion intervention to monitor pregnancy weight gain (Fealy et al, 2020). Women in Australia reported feeling reassured if their weight gain as measured during antenatal care was within normal parameters (Allen-Walker et al, 2020). However, weighing is no longer part of routine antenatal care in Ireland. With the introduction of routine weighing at the advanced midwifery practitioner service for the present study, no woman declined to be weighed, and many were keen to discover their weight at each appointment. This was a direct observation by the advanced midwife practitioner who provided continuity of care for all women attending this service. Routine weighing in pregnancy has been shown to be an excellent opportunity to prompt health-promoting discussions about diet and physical activity, and helps to ensure normal gestational weight gain (Aung et al, 2021). If weight gain was outside of recommended values, this awareness can motivate a woman to alter her diet and explore healthy behaviours with her healthcare professional (Allen-Walker et al, 2020).

In the present study, the advanced midwife practitioner used ‘making every contact count’ (HSE, 2016) as a framework to discuss weight gain. No woman declined to discuss healthy eating or explore areas that may be contributing to excess weight gain. As all service users were aware of the recommended weight gain, many initiated discussions about healthy eating and exercise before the advanced midwife practitioner could calculate their weight gain. By the 28-week visit, some women attending the service were almost at their maximum recommended weight. As an example of how useful the intervention was, one woman's partner had been bringing her home a muffin every night as a treat. When she realised the muffin contained 600 calories, she signposted her partner to healthy eating and exercise in pregnancy. They developed a non-food related reward scheme based on the number of steps they achieved and the number of fruit and vegetable portions they consumed daily. She did gain approximately 1kg over the IOM recommendations, but she reported enjoying the challenge and lifestyle changes made during the third trimester and had a vaginal birth of a 3.45kg baby.

Another woman with a similar weight gain by 28 weeks had a different story. Pre-pregnancy, she normally only ate one meal a day. Following antenatal care attendance, she was eating three balanced meals a day with normal portion sizes, plenty of fruit and vegetables and no confectionary. She was also exercising, so there were no identifiable changes to be made. Despite gaining excess weight, she had a vaginal birth of a 3.2kg baby with no complications.

The introduction of routine weighing to advanced midwife practitioner care during the present study added a new health promotion dimension and ensured compliance with the making every contact count initiative (HSE, 2016). It facilitated discussions and problem solving, with all women now being signposted to healthy eating and exercise, not just those that had excess weight gain.

Weighing in pregnancy prompts care givers to screen for adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes if weight gain is above or below IOM recommendations (Fealy et al, 2020). Prior to routine weighing, suspected small or large babies were identified by discrepancies in the symphysis fundal height, which would trigger a growth ultrasound request (Perinatal Institute for Maternal and Child Health, 2020). Since the introduction of routine weighing, one woman with a recommended weight gain of up to 16kg, had only gained 4.5kg by 34 weeks. The symphysis fundal height was 33cm but a scan was requested and performed at almost 36 weeks. The fetus was small for gestational age, with the estimated fetal weight being less than the 5th percentile and the abdominal circumference equal to the 5th percentile. These parameters had been closer to 45% at the anomaly scan performed at 21 weeks. A plan was made for a repeat growth scan at 38 weeks, but the woman presented in spontaneous labour that day and had a 2.55kg baby. Without routine weighing, the scan would not have been triggered for the lack of gestational weight gain, and a small for gestational age baby may have been missed and not managed as per best practice.

All women in this study received continuity of care from the advanced midwife practitioner. The trusting relationship arising from continuity of carer throughout pregnancy, with health promoting conversations, is effective in maintaining gestational weight gain within IOM guidance (Aung et al, 2021). As a result, the present study's findings may be influenced by this model of care giving, and the results may not replicable in services that use non-continuity of care models. However, the results are positive and comparable to international studies. The main benefit is health promotion, which has the potential to impact the future health of women and their families. Antenatal care presents healthcare professionals with a unique opportunity during pregnancy to signpost women towards healthy eating and lifestyles. If more women can be assisted to gain weight as per IOM recommendations, this is likely to have an effect on birth outcomes for women and babies. There are lifelong benefits for the woman and also a cost-saving implication for the maternity care setting.

Limitations

This was a small-scale study with all the participants receiving continuity of care from the advanced midwife practitioner. Therefore, this may not be replicable in other models of care.

Conclusions

Based on a global rise in obesity, as well as caesarean section birth rates, international research findings and those from this small audit study indicate that maternity services may wish to reconsider monitoring weight gain in pregnancy. This will ensure that pregnancy is used as an opportunity to encourage ongoing healthy eating and exercise to reduce lifelong maternal and childhood complications associated with excess pregnancy weight gain.

The combination of routine weighing and ongoing health promotion should ensure weight gain in pregnancy according to IOM guidelines. If implemented routinely, it has the potential to replicate international findings and could reduce the number of caesarean section births, blood pressure complications, large for gestational age babies and post-pregnancy weight retention. As healthcare professionals, reintroducing routine antenatal weighing should be considered and viewed as a long-term investment in the future health and wellbeing of mothers and babies.

Key points

- Routine weighing in pregnancy should be viewed as a health promotion opportunity to signpost a woman and her family to healthy eating and lifestyle changes that could have a positive impact on the family's future wellbeing.

- By ensuring pregnancy weight gain is within Institute of Medicine guidelines, there is the potential to reduce the risk of hypertension, caesarean section birth, large for gestational baby and neonatal intensive care admission.

- Follow-up studies have identified a link between excess weight gain in pregnancy and ongoing postnatal obesity and weight retention, diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease.

- Excessive pregnancy weight gain also increases fat stores in the baby and is linked to childhood obesity and hypertension.

CPD reflective questions

- Could routine weighing be beneficial to your service users?

- How would you feel if you were asked to implement routine weighing at the antenatal clinic?

- What training would you need to feel confident in providing information to your service users about healthy eating and exercise in pregnancy?

- Is weight gain something that you feel comfortable discussing or what skills would you require to enable you to do so?

- If you implemented routine weighing in your unit, how would you evaluate the impact of this intervention in your service?