Breastfeeding is a public health priority in the UK (Public Health England, 2016). While the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends using peer support to increase both initiation and duration of breastfeeding (WHO, 2015), a survey of infant feeding co-ordinators in the UK concluded that more evidence was needed to inform the provision of breastfeeding peer-support services (Grant et al, 2017). An evidence-based model called the ‘Solihull Approach’ (Douglas, 2012) has been used in one Local Authority as a basis for the training of breastfeeding supporters. Anecdotal reports suggested that this was helpful and contributed to earning the service a Baby Friendly Award, a best practice accreditation scheme of the Baby Friendly Initiative (UNICEF UK, 2017). A formal qualitative study has been conducted on the experiences of the Solihull Approach-based breastfeeding support group (Thelwell et al, 2017) from the point of view of the breastfeeding peer supporters. This article reports the mothers' perspectives.

Background

Despite increasing awareness of the health benefits of breastfeeding (Brown, 2015), only about one-third (34%) of British mothers are still breastfeeding at 6 months (McAndrew et al, 2012) and 0.5% at 12 months, making it the lowest rate in the world (Victora et al, 2016). Furthermore, health inequalities prevail, as young, single mothers with low educational achievement are less likely to breastfeed, especially in areas of high deprivation where formula feeding is the norm (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2008; Brown et al, 2010; Stuebe and Bonuck, 2011). Proactive provision of skilled peer or professional support is effective in increasing breastfeeding duration rates (Renfrew et al, 2012). To the best of our knowledge, however, most research focused on one-to-one support. The few studies conducted on the effectiveness of breastfeeding support groups reported inconsistent results, as it seemed to largely depend on how the support groups were implemented, since the organisation of maternity services affects the quality of the partnership between midwives, health visitors and women (Alexander et al, 2003; Ingram et al, 2005; Hoddinott et al, 2006a; Hoddinott et al, 2009). It might therefore be more informative to shift from whether breastfeeding support groups are effective, to what can make them helpful.

A few studies provide useful starting points: mothers have been found to appreciate being able to talk about breastfeeding, see it happen, increase their confidence in breastfeeding practices, and socialise (Ingram et al, 2005). Additionally, special training in breastfeeding counselling reportedly makes supporters more helpful (Ekstrom et al, 2006). While professional facilitators can act as gatherers of community experience, normalising or counteracting extreme views and distinguishing facts from anecdotes and myths (Hoddinott et al, 2006b), trained peer supporters are helpful too: thanks to their experiential insights, they are able to inform from a breastfeeding mother's perspective (rather than a clinician's). They also tend to forge mutually supportive relationships with the mothers, which provides the basis for more holistic and emotionally-based care (Thomson et al, 2012).

More research is needed to strengthen the evidence base on breastfeeding support groups, given the inconsistency in the results of the most robust studies (Hoddinott et al, 2009; Hoddinott et al, 2006a). The breastfeeding support groups that have been studied were also rarely underpinned by any model of support. Yet, a model could help systematise the most helpful aspects in breastfeeding support groups.

The Solihull Approach

The Solihull Approach (Douglas, 2012) is an integrated psychotherapeutic and behavioural model that is widely used in work with infants and parents. First developed in the 1990s for health visitors to work on parent-child relationships, its scope and application have steadily broadened and it is now used in the training of most health visitors, child, and family practitioners across the UK. By providing a strong theoretical framework for working with emotional and behavioural difficulties, the aim of the Solihull Approach is to increase emotional health and wellbeing. It is based on three theoretical components: containment, reciprocity and behaviour.

The Solihull Approach therefore focuses on mothers experiencing emotional containment, which facilitates the development of reciprocity within a relationship, and in turn creates a framework for effective and sensitive behaviour change.

The Solihull Approach has the potential to make breastfeeding support conducive to emotional health and well-being in a more systematic fashion. To the best of the authors' knowledge, no study has been published on breastfeeding support groups that is informed by such a strong theoretical model on emotional wellbeing. The aim was therefore to explore maternal perceptions of a breastfeeding support initiative underpinned by the Solihull Approach.

Methods

Study context

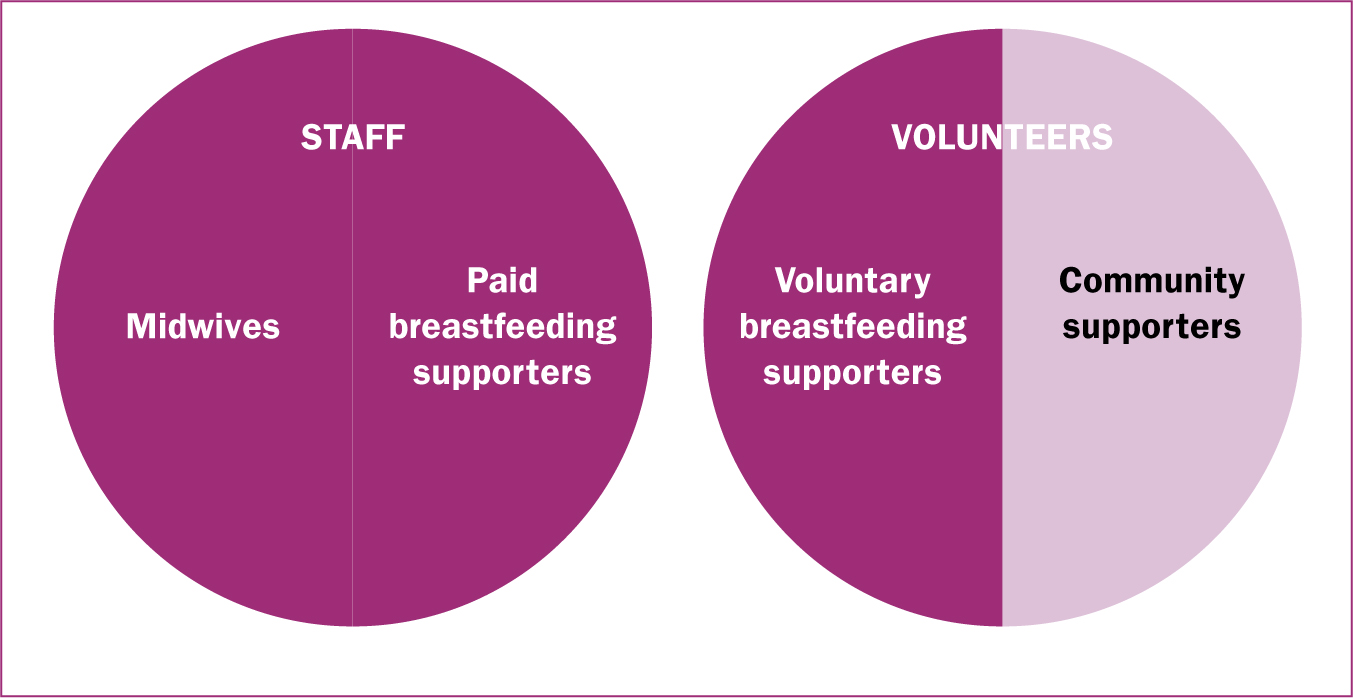

The breastfeeding cafés used in this study are drop-in venues, open 4 days per week in various parts of Solihull, West Midlands, and run by midwives and peer breastfeeding supporters trained in the Solihull Approach. Community volunteers also assist as hosts in the most popular venues (Figure 1).

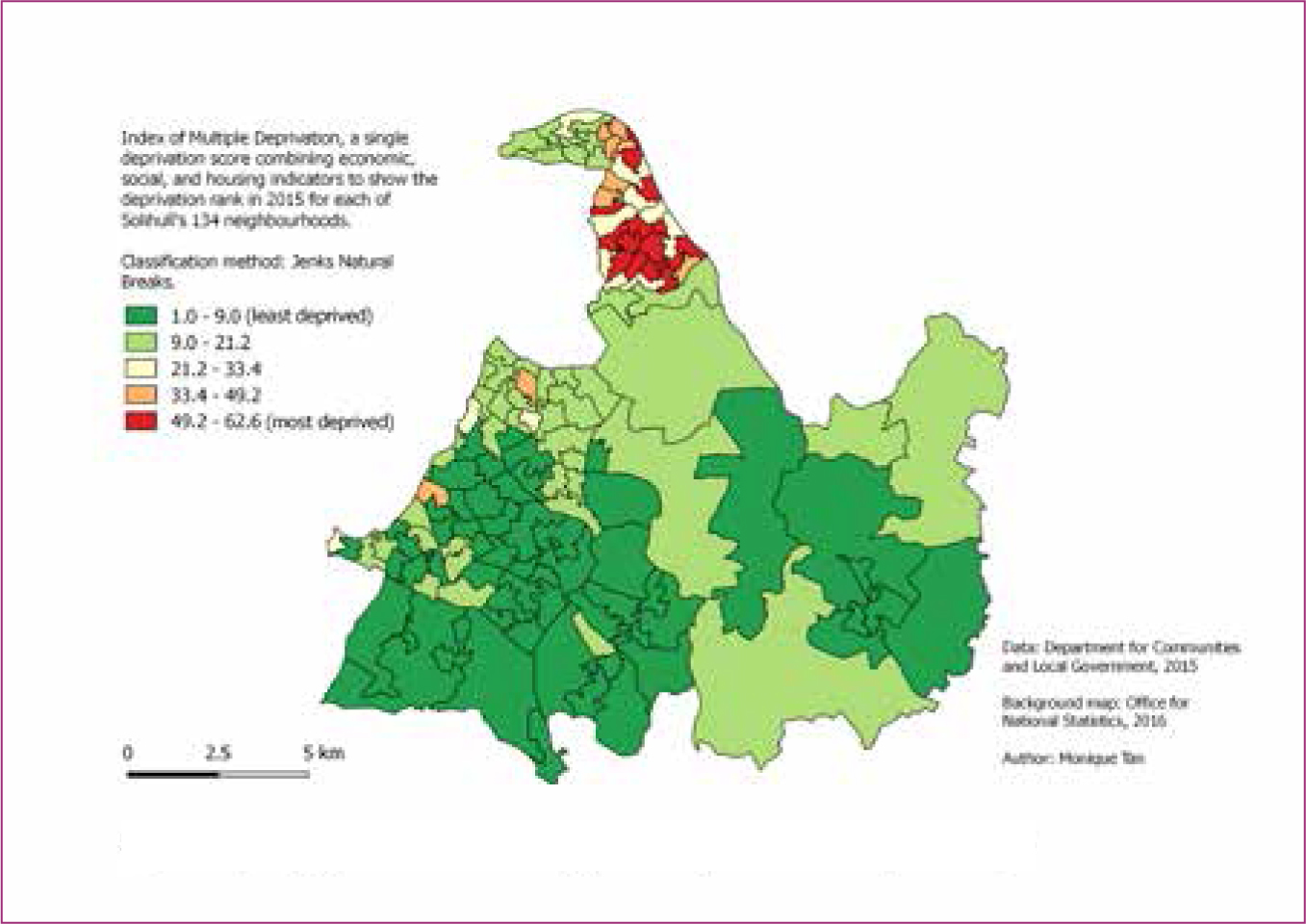

The broadly affluent borough of Solihull is challenged by a prosperity gap, with its northern part being considered a regeneration area (Figure 2) (Solihull Observatory, 2016).

Participants recruitment

A sample of nine mothers was interviewed in November 2016. Recruitment took place in the breastfeeding cafés (with the exception of one mother who was contacted by phone by a midwife). A subgroup sampling design (Onwuegbuzie and Leech, 2007) was used in order to facilitate credible comparisons between mothers from north Solihull and those from south Solihull. Four out of five mothers attending the breastfeeding café in north Solihull were interviewed and, in order not to over-represent the affluent participants in the analysis, this was matched with a convenience sample of five mothers in south Solihull. Reasons given for non-participation included not feeling experienced enough about the breastfeeding cafés to talk about it, being too busy, and having recently been interviewed about the breastfeeding cafés by the Solihull Metropolitan Borough Council for their annual report.

Table 1 contains information on the participants. Aged 28 to 43, their first attendance to the café dated from 1 week to 6 years before interview. Women reported first hearing about the breastfeeding cafés from a friend, the family information service, or a health visitor or midwife during a home visit, and all but one attended the breastfeeding cafés weekly or fortnightly.

| Mother | Solihull area | Age | Date of first attendance | Reason for first attendance | Child's age at first attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | North | 28 | August 2016 | Suspicion of tongue tie | 5 weeks |

| 2 | South | 34 | 2010 | Difficulties in breastfeeding | 1–2 week(s) |

| 3 | South | 29 | August 2016 | Pain during breastfeeding | 2 weeks |

| 4 | South | 34 | 2012 | Cluster feeding, proving to herself she could get out of the house | 13 days |

| 5 | South | 31 | November 2016 | Pain during breastfeeding | 6 weeks |

| 6 | South | 36 | November 2016 | Pain during breastfeeding | 2 days |

| 7 | North | 34 | 2014 | Seeking information on breastfeeding | Not born yet |

| 8 | North | 43 | June 2016 | Concerns about the quantity of breast milk, social contact | 5 months |

| 9 | North | 29 | September 2016 | Practice feeding out of her house | 4 months |

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in a separate room at the breastfeeding café venues. They lasted 20-40 minutes, were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. A testimonial about the breastfeeding cafés shared by one of the participants has also been included in the data analysis. Before the interviews, two breastfeeding café sessions (one in north Solihull and one in south Solihull) were visited by the main investigator to gather observational data, which consisted of overt participant observation as well as informal and opportunistic conversations. The purpose of the observation was to understand the context in which breastfeeding support occurred. This helped to improve the nature and the phrasing of the interview questions, provide a yardstick against which to measure the completeness of the data gathered with the interviews, and to create opportunities to talk about the study and recruit participants.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) was used in an inductive fashion, which included coding, theme formation, and generation of a thematic map (Table 2).

| Transcript | Generating initial codes | Searching for themes | Final theme | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Boobs are, sort of, just for sexual pleasure aren't they, you know, they are on page 3, you see them on billboards everywhere, sexy underwear … so it's almost like they are not for what they are meant …’ (Participant 1) | Breasts are sexualised | Pervasive bottle-feeding culture | Social climate that normalises breastfeeding amid a bottle-feeding culture | ‘For once, we are the majority’: isolation of the breastfeeding mother in a bottle-feeding culture |

| ‘When I just started breastfeeding, I think it was just a bit out of the blue for everybody. […] It's not as normal … so, it was a bit more … a bit more discussion, and a bit more, sort of, uncomfortableness for, for the family, and friends’ (Participant 1) | Friends and family uncomfortable with breastfeeding | |||

| ‘So my mum bottle-fed. A lot of my family bottle-fed. It was only my aunt, who lives you know Stratford way, that I'd got as a … as a help in my family!’ (Participant 9) | Breastfeeding isn't the norm anymore | |||

| ‘My mum is a real advocate of breastfeeding but it's a long time since she's done it and she wasn't really able to offer me the support that I needed with this. She's been great but she can't check for tongue tie you know’ (Participant 5) | Family unable to help | Isolation as a breastfeeding mother | ||

| ‘Unfortunately you know my partner and my mum were quick to say ‘well why, you know, why don't you just give up breastfeeding and formula feed, you know, it won't do him any harm’’ (Participant 8) | Partner and mother quick to suggest quitting breastfeeding | |||

| ‘It is how friendly the support staff are. That for me is the best thing. You come in, they recognise you. […] they sit you down with somebody and introduce you to, you know, and make you sort of be part of the group straight away.’ (Participant 5) | Breastfeeding café staff makes you feel welcome and at ease | Breastfeeding café as a safe and welcoming place | ||

| ‘The first time I came back, this time, um, people … were just very friendly. ‘cause I've obviously haven't been here for four years.’ (Participant 2) | Still welcome at the breastfeeding café after years of absence | |||

| Strong network of peer breastfeeding mothers and supporters | ||||

| Breastfeeding mothers' isolation, anxiety, and vulnerability | ||||

Ethical considerations

This study was part of a service evaluation, so ethical approval was not required. Nevertheless, all steps were taken to ensure coverage of ethical considerations, including written informed consent forms and confidentiality for all participants. Participant observation was overt and anyone contributing to the observational data was informed about the study.

Results

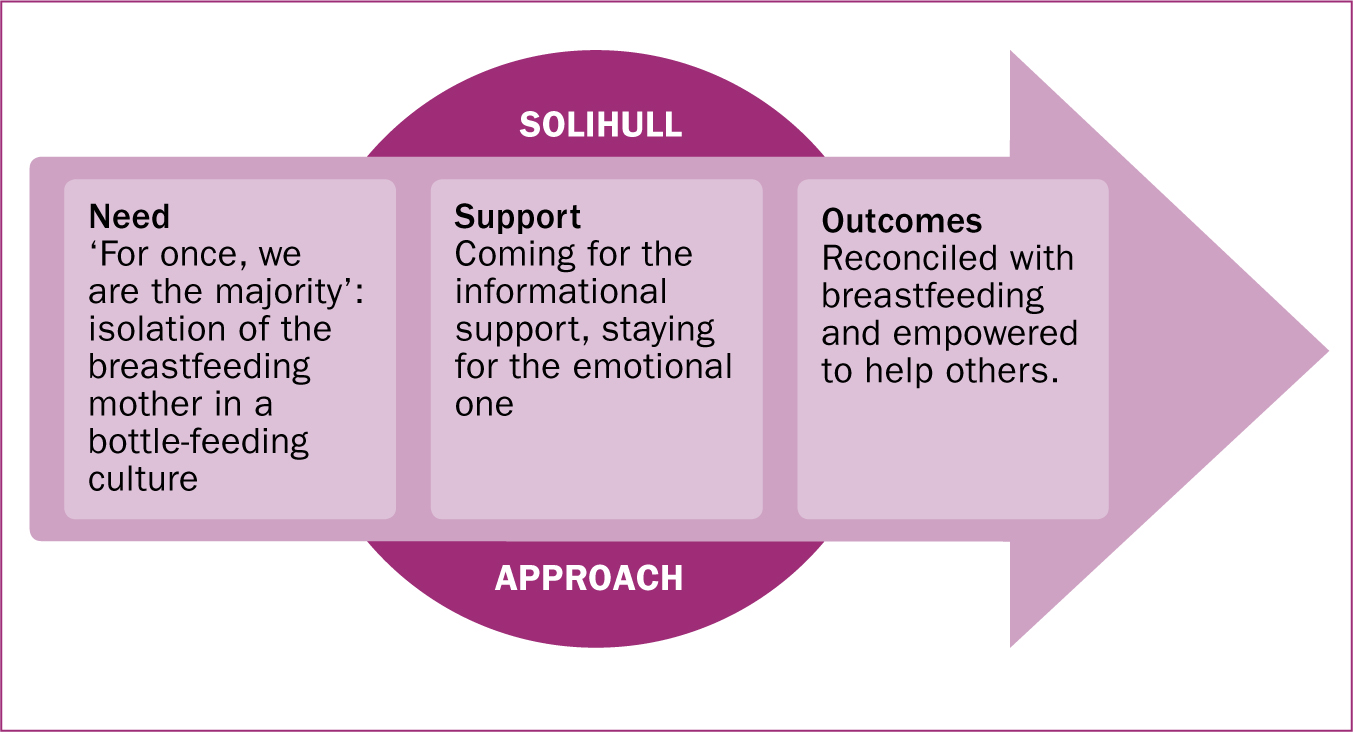

Three prominent themes were found and arranged in a conceptual model (Figure 3). ‘Peerness’ in the breastfeeding cafés was related to personal experience of breastfeeding, rather than shared socioeconomic background. While mothers in south Solihull were generally more familiar with breastfeeding, mothers in north Solihull struggled to find any breastfeeding role models among family, friends, and health professionals. Nonetheless, as breastfeeding mothers, all participants felt isolated in the prevailing bottle-feeding culture.

‘For once, we are the majority’: isolation of the breastfeeding mother in a bottle-feeding culture

There was a self-imposed pressure to be the perfect mother, which could become particularly demoralising when breastfeeding and parenting proved to be more difficult than expected.

‘You are putting a lot of pressure on yourself as a mum anyway. You want to do what's best for them. And, and like I've said, if I would have stopped breastfeeding, I would have felt like such a failure [emphasis original].’

Participants also felt isolated due to important events that came with motherhood, such as transitioning from full-time employment to maternity leave, or due to their shifting priorities and interests.

‘Your group of friends change […] you are not boring your friends that are, I don't know, in college or like, they are unaware of … their priorities is to going out, drinking, and … you are on different, yeah, different pages at that point.’

Another cause of their isolation was the bottle-feeding culture, which seemed more pervasive in north Solihull.

‘I don't know about you but I only saw one woman breastfeed before I had my own […] So my mum bottle-fed. A lot of my family bottle-fed.’

In this social climate, the breastfeeding cafés were described as ‘inviting’ and ‘welcoming’, a culture that was informed by the Solihull Approach. There, breastfeeding was the norm and the mothers felt at ease and accepted, even when they were ‘feeling down’, ‘quiet’, ‘nervous’, ‘upset’, had been absent for several years, or were no longer experiencing problems with breastfeeding.

‘It doesn't seem to matter whether you come every week or whether you just come for the first time. […] When new mums come for the first time, they feel … welcome […] The first time I came back, this time, um, people … were just very friendly. ‘Cause I obviously haven't been here for four years.’

The staff and volunteers at the breastfeeding cafés were seen by participants in this study as being available, reliable, and trustworthy. Their availability was demonstrated in three ways: the breastfeeding cafés being held 4 days per week; their ability to assist everyone, even when attendance was high; and the possibility for breastfeeding mothers to reach the staff and volunteers by phone or text messages.

‘They are on every day, various places around … There is always somebody there who would answer your questions, […] watch your baby latch on and, you know, any, any kind of query you might have or concern, um, you can go to the cafés and you can ask, or get, get reassurance from them, which is brilliant.’

The staff's reliability and trustworthiness was seen by participants in this study as being related to their theoretical and experiential knowledge on breastfeeding. Some mothers forged a trusting relationship with particular staff members. That some staff seemed to view the mothers with an unconditionally positive regard was also of importance. This was most evident in the community volunteers, who described themselves as maternal figures during one of the participation observation sessions.

‘I remember walking nervously through the doors and being greeted by the biggest smile and most reassuring hug from [community volunteer], it was all too much and the tears began, a packet of tissues was provided, hot tea (which any parent will know is very rare), and wonderful non-judgemental ears. It was the first time in weeks that I felt like me again and not just Mummy or a milk machine!’

Seeking information, finding emotional support

Informational support was what most mothers were seeking when they attended breastfeeding cafés for the first time. Information from the staff was said to be accurate, up-to-date, and personalised, comprising medical diagnoses by a midwife (such as that of tongue ties), factual input (for example how common cluster feeding is), technical advice (including practical demonstrations of latching and positioning), and feedback on performance, with comments such as ‘you are doing fine’. The quality of the information at the breastfeeding cafés was said to surpass that of GPs, and participants reported that they preferred its delivery to that of ‘over-stretched’, ‘pushy’ hospital midwives or from telephone or online support.

‘It's nice to speak to people face-to-face as well. Rather than just, you know, over a, just a telephone, or blogs or forums.’

The Solihull Approach was seen in the emotional support provided. Mothers were able to discuss their personal difficulties in an attuned relationship (in reciprocity) with the supporters, who practised containment by avoiding exhortatory advice-giving, which led to tailored advice.

‘You know if there is anything ever, ever wrong, it's almost like that friend that you can confide in. I feel like I can … I've only known [paid breastfeeding supporter] for a couple of months and I can tell her anything. She listens [emphasis original] … it's not about her story, and she'll jump in with advice, which is brilliant, but she doesn't take over, she's just there to listen and to let me offload … and she seems very interested at the time [laughs]’

Emotional support was also provided in the form of encouragement, reassurance, and verbal and non-verbal expressions of caring. As one mother explained:

‘It's silly things like that, it really is, just someone holding the baby for 5 minutes so you can sit down and drink a cup of tea and it's hot and it's just … it's great.’

Reconciled with breastfeeding and empowered to help others

Support from the breastfeeding cafés improved the mothers' breastfeeding via three different mechanisms.

First is by direct effect: medical advice, information, and practical demonstrations influenced breastfeeding practices and deterred maladaptive behaviours. Attending the breastfeeding cafés also directly decreased the mothers' feelings of isolation.

‘When you are a new mum and you kind of have these expectations of how it's going to be like. And there are days when it's going to be really hard and you're going to say that it was quite nice to be with people in the same boat.’

Second is the buffering effect: protecting mothers from harmful stressors by providing information on the nature of their problems and by discussing problem-solving strategies. Additionally, by being at the breastfeeding café, the mothers conformed to social controls and pressures, which induced normative behaviours by response regulation and prevented maladaptive responses such as extreme reactions or self-recrimination.

‘[It] made me feel like it's not just me, so there was everybody else talking about how it's hard for them as well […] I was quite … at the end of my tether. When I've been here in the morning, I went away feeling like pretty happy and kind of ready to … yeah, be able to … to do it.’

Third is the mediating effect, in which the mothers' interpretation of their issues is positively influenced with the aim of increasing their self-confidence in breastfeeding. This was done by providing anticipatory guidance, normalising certain emotional arousals, and appraising their breastfeeding performance. Being surrounded by other mothers also gave the opportunity of social comparison, which was helpful for self-evaluation and motivation.

‘I don't want to sound horrible, but when you see other people struggling as well, then you know … “Oh … it's not just me. It's everyone.” You feel … that gave me more confidence, definitely.’

One aspect that made the breastfeeding cafés helpful and that differentiated them from one-to-one support was the multiplicity of the sources of support:

‘All of them are helpful. Because … I don't know […] You've got obviously the people who work here who are going to be helpful, the volunteers are helpful, but the other mums are helpful too, you know, everybody is going to bring up different perspectives, have different experiences.’

Another outcome was the desire generated in the mothers to help other breastfeeding women. This desire was manifested in several ways: by feeling able to advise other mothers at the breastfeeding cafés; by suggesting during the interviews different ways the breastfeeding cafés could be better promoted (despite the already high attendance or the small size of some venues); by seeking connections with other women they witnessed breastfeeding in public; and by training themselves to become volunteer peer breastfeeding supporters.

‘I started [the training …] Really, really good move to make, ‘cause I thought, I'm quite passionate about breastfeeding, and I had such a troublesome time at the beginning, that without this sort of service I would have quit. So it's nice to be able to see other mums, and give that bit back.’

Discussion

Given the low breastfeeding rates, it is important to understand what can make breastfeeding support helpful. The study aimed to explore maternal perceptions of a breastfeeding support initiative in Solihull, which was provided through peer support groups in drop-in venues, and was informed by a particular theoretical model. Qualitative data were collected through semi-structured interviews and participant observation. It was found that the breastfeeding cafés represented safe environments where breastfeeding mothers in need of emotional and information support could find a network of peers, and that such support not only improved their breastfeeding outcomes but also generated a desire to help others.

Underpinning the training of all breastfeeding café staff with the same theoretical model ensured consistency in the support provided across all types of staff in every venue. Therefore, even if a mother became closer to a particular supporter, she knew she could find the same quality of support with another supporter in any other breastfeeding café. Benefits that were more specific to the use of the Solihull Approach were also evident. Containment created safe spaces, figuratively (between a supporter and a mother) but also literally—the inviting atmosphere reigning at the breastfeeding cafés made all participants feel welcome and accepted. Knowing that breastfeeding café staff were reachable at all times (if not at a breastfeeding café held somewhere that day, then by telephone) was yet another form of containment. Containment and reciprocity enabled the breastfeeding café staff to provide emotional support in a way that satisfied all participants and made them continue attending the breastfeeding café even after their initial problems were solved. Sustained attendance at the breastfeeding support group may support persistence in breastfeeding. Containment and reciprocity also helped the staff to tailor their informational and emotional support to each mother and make it appropriate for each situation (for example making a diagnosis, demonstrating, giving feedback on performance, following-up on an issue, but also chatting and developing trusting relationships), leading to effective behaviour change.

Most findings concurred with existing literature, notably in terms of the vulnerability of new parents (Ekström et al, 2006); the positive atmosphere of the breastfeeding support group (Hoddinott and Pill, 1999), where mothers felt they could talk openly and practice their breastfeeding skills (Ingram et al, 2005; Hoddinott, 2006b); the appreciation for supporters with personal breastfeeding experience, whether health professionals (Hoddinott, 2006b), trained volunteers (Mongeon and Allard, 1995), or other mothers (Timms, 2002); the forging of trusting relationships between mothers attending the same support group (Thomson et al, 2012) and between mothers and supporters (Schmied et al, 2011).

Elements reminiscent of the Solihull Approach could also be found in previous studies: breastfeeding supporters have been described as the ‘calm in the storm’ because they helped the mothers regain composure, re-establish focus, and direct their energy towards breastfeeding (Thomson et al, 2012). Giving time for the mothers to ‘touch base’ and not feel rushed was another component of effective breastfeeding support, in contrast to disconnected and time-constrained encounters in medical settings (Schmied et al, 2011). Other concordant observations were the ‘upwards and downwards’ comparisons, which, according to social comparison theory (Perry and Furukawa, 1986), explains why mothers who were perceived to perform better were considered role models, while self-esteem and motivation were enhanced when perceiving others' breastfeeding performance as worse. The mediating effect relates to the concept of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977), where affirmation, reassurance, encouragement, and social integration enhanced mothers' perception of their own ability, which increased initiation and perseverance in attempts, leading to better performances.

Strengths and limitations

The transferability of findings is limited by a selection bias, as sampling relied heavily on onsite recruitment, thereby automatically excluding all those who never attended or ceased attending the breastfeeding cafés (because they did not find them helpful, for example). Although most participants in this study enjoyed leaving their home to socialise at the breastfeeding cafés; for other mothers, the requirement to attend group support sessions could be too great a constraint.

Strengths of the study include the use of a conceptual model to make sense of the inductive findings, which has not been done in previous studies on breastfeeding support, except for Thomson et al (2012) who used a theory of hope. What happens in breastfeeding support groups can be difficult to understand, as it can be approached from a certain number of ways. Explicitly using conceptual models can improve understanding and highlight the most important aspects. This study was the first in the literature to distinguish between the reasons for first attendance and those for sustained attendance.

Conclusion

This study highlights the importance of emotional support to increase attendance at breastfeeding support groups, and of models such as the Solihull Approach in developing a supportive culture. Provision of breastfeeding support would benefit from being underpinned by a theoretical model in order to systematise the most helpful aspects of breastfeeding support. The Solihull Approach is a promising candidate to serve as such a model: this study showed that it can ensure consistent and tailored informational support as well as responsive emotional support across all staff of breastfeeding support groups—which mothers of highly-contrasting socioeconomic backgrounds greatly enjoyed. Suggestions for future research include approaching women who never attended, or are no longer attending, breastfeeding support groups.