Adolescent pregnancy (at 10–19 years old) is a major health concern that leads to significant biological, psychological and social impacts, as well as contributing to the cycle of poverty (Rosales-Silva and Irigoyen-Coria, 2013; Baba et al, 2014). Early adolescents (defined as those aged 10–14 years) are considered particularly vulnerable compared to their older counterparts (Latin American Consortium Against Unsafe Abortion, 2019). Each year, approximately one million girls under 15 years old give birth, most in low- and middle-income countries (World Health Organization, 2020).

The pregnancy rate for early adolescents in Latin America and the Caribbean is the second highest worldwide (2% of all women), only surpassed by sub-Saharan Africa, and is the only region with an upward trend (Pan American Health Organization, 2018). According to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (2017), adolescent pregnancy is predominant in socioeconomically disadvantaged sectors, where the pregnancy rate in the poorest quintile is four times higher than in the wealthiest quintile. Adolescent pregnancy is more prevalent among women with low educational levels in low- and middle-income countries, where approximately 14% of adolescents marry before they are 15 years old (Latin American Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology Societies, 2011; World Health Organization, 2020).

Global interest in addressing the lack of information about adolescent pregnancy is reflected in the sustainable development goal indicators (United Nations, 2017), highlighting the need for comprehensive studies on this phenomenon, especially in Peru, which has one of the highest adolescent pregnancy rates in South America at 0.3% (Pan American Health Organization, 2018). Adolescent pregnancy rates vary across countries and social contexts, emphasising the importance of understanding the specific epidemiology in each country and identifying areas where greater emphasis on education and monitoring is needed to tackle this public health issue.

The aim of this study was to identify associations between adolescent pregnancy in girls under 15 years old in Peru and socioeconomic, gender inequality and reproductive health indicators.

Methods

This retrospective ecological study examined factors associated with pregnancy in girls <15 years old in Peru.

Data collection

The pregnancy rate among early adolescents (aged 10–14 years) from 2017–2021 was obtained using data from the Peruvian online registry system of birth certificates. This system is a collaborative effort between the National Registry of Identification and Civil Status and the Ministry of Health of Peru, which enables prompt registration of newborns in healthcare facilities. This process helps minimise errors in certificate issuance compared to manual registration methods.

Exposure variables were categorised into three groups: socioeconomic, gender inequality and reproductive health indicators. The specific variables and sources where data were taken are shown in Table 1.

| Category | Variable | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic | Human development index | Global Data Lab (2022) |

| Life expectancy at birth | Editorial Management (2021) | |

| Family income per capita | National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (2022a) | |

| Population living in monetary poverty | Peruvian Economic Institute (2022) | |

| Expected years of schooling | National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (2022b) | |

| Average years of schooling in those aged ≥25 years | National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (2022b) | |

| Complete secondary education in those aged ≥18 years | National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (2022b) | |

| Gender inequality | Inequality-adjusted human development index | United Nations Development Programme (2019) and United Nations Population Fund (2022) |

| Labour force participation in women aged ≥15 years | National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (2022c) | |

| Literacy in women aged ≥15 years | National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (2022d) | |

| Reproductive health | Rate of contraceptive use in women with a partner aged 15–49 years (including modern and traditional methods) | National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (2022e) |

| Coverage of prenatal care with at least one visit | National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (2022c) | |

| Births attended by specialised healthcare professionals | National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (2022c) |

Data analysis

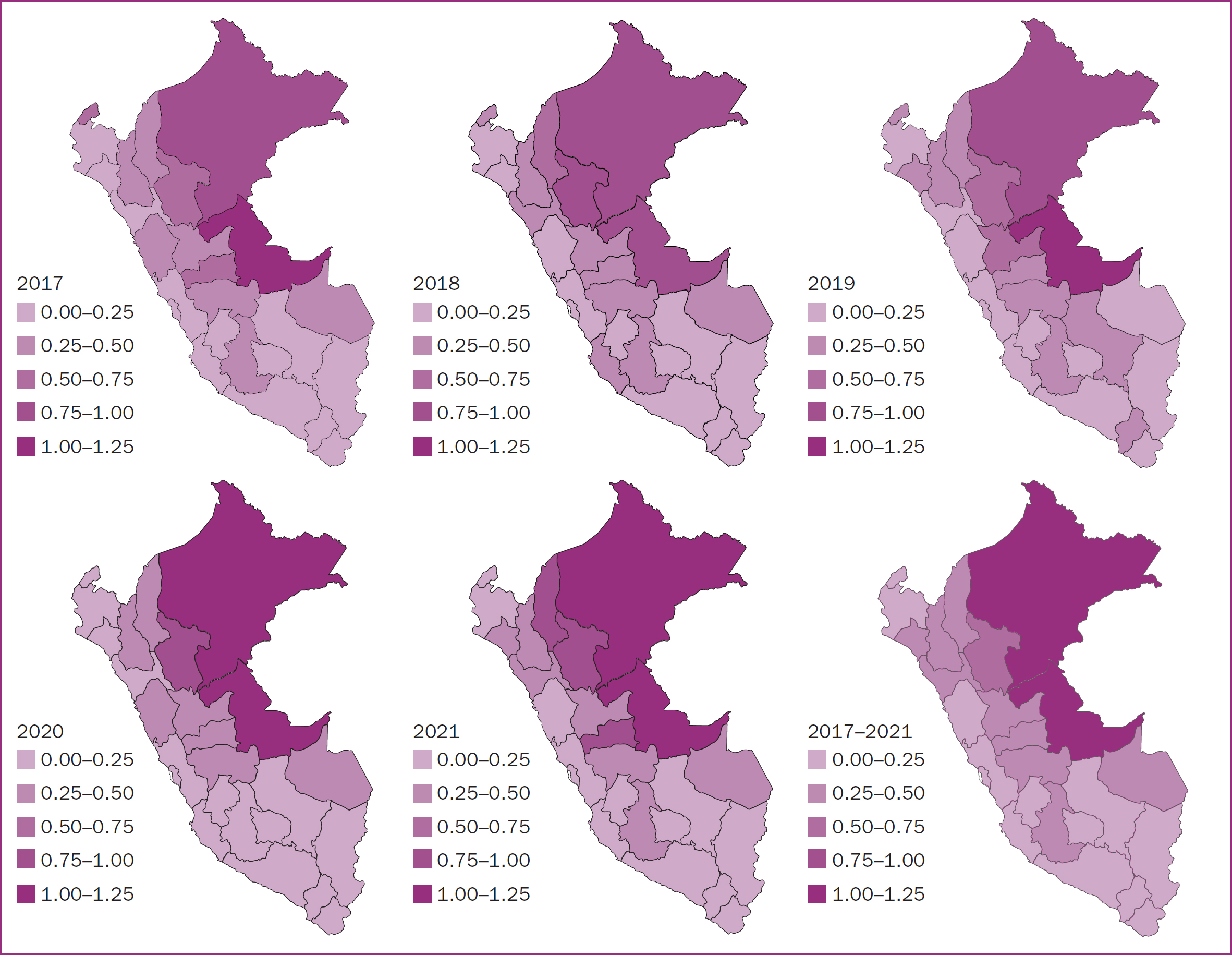

Normality of numerical variables was assessed using the Skewness and Kurtosis hypothesis test. Medians were calculated for age at time of birth, adolescent pregnancy rate and study population indicators. Maps were used to describe the pregnancy rate in adolescents aged 10–14 years per 100 live births, categorised by year and geographical region. Available indicators were organised and compiled based on geographical region.

Simple linear regression models with beta coefficients (β) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated to explore associations between indicators and the adolescent pregnancy rate by geographical region. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis and map generation were performed using RStudio 4.2.0.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Universidad Privada de Tacna (reference: 056-FACSA-UI) Dynamic queries from the registration system were used to obtain information, excluding identification data, preserving the confidentiality, anonymity and rights of participating women.

Results

A total of 6614 Peruvian early adolescents gave birth between 2017 and 2021, with the highest number of births occurring in 2021 (n=1430). The median age at birth was 14 years. Table 2 provides a detailed overview of the socioeconomic, gender inequality and reproductive health indicators observed over the 5-year study period.

| Variable | Median | Interquartile range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent (10–14 years) pregnancy rate (births per 100 live births) | 0.25 | 0.16–0.39 | |

| Socioeconomic indicators | Human development index | 0.76 | 0.74–0.79 |

| Life expectancy at birth (years) | 75.30 | 74.30–77.00 | |

| Family income per capita (Peruvian Nuevo Sol per month) | 937.00 | 795.00–1016.00 | |

| Population living in monetary poverty (%) | 25.30 | 19.30–34.60 | |

| Expected years of schooling | 15.52 | 15.15–16.37 | |

| Average years of schooling in those aged ≥25 years | 9.40 | 8.80–10.00 | |

| Complete secondary education (% of those aged ≥18 years) | 65.47 | 58.61–72.77 | |

| Gender inequality indicators | Inequality-adjusted human development index | 0.28 | 0.26–0.30 |

| Labour force participation in women aged ≥15 years (%) | 58.26 | 50.70–66.12 | |

| Literacy in women aged ≥15 years (%) | 90.63 | 85.72–95.04 | |

| Reproductive health indicators | Contraceptive use among women with a partner aged 15–49 years (% | 77.60 | 75.30–79.90 |

| Modern contraceptives | 56.00 | 52.50–60.30 | |

| Traditional contraceptives | 22.60 | 17.90–26.20 | |

| Coverage of prenatal care with at least one visit (%) | 99.17 | 98.37–99.59 | |

| Births attended by specialised healthcare professionals (%) | 97.71 | 93.68–99.41 | |

Adolescent pregnancy by geographical region

The pregnancy rate was 0.28 per 100 live births from 2017 to 2021, with the highest rate observed in 2021 at 0.31 per 100 live births (supplementary material). Regions in the jungle, such as Ucayali and Loreto, had the highest rates (Figure 1).

Associations between pregnancy and indicators

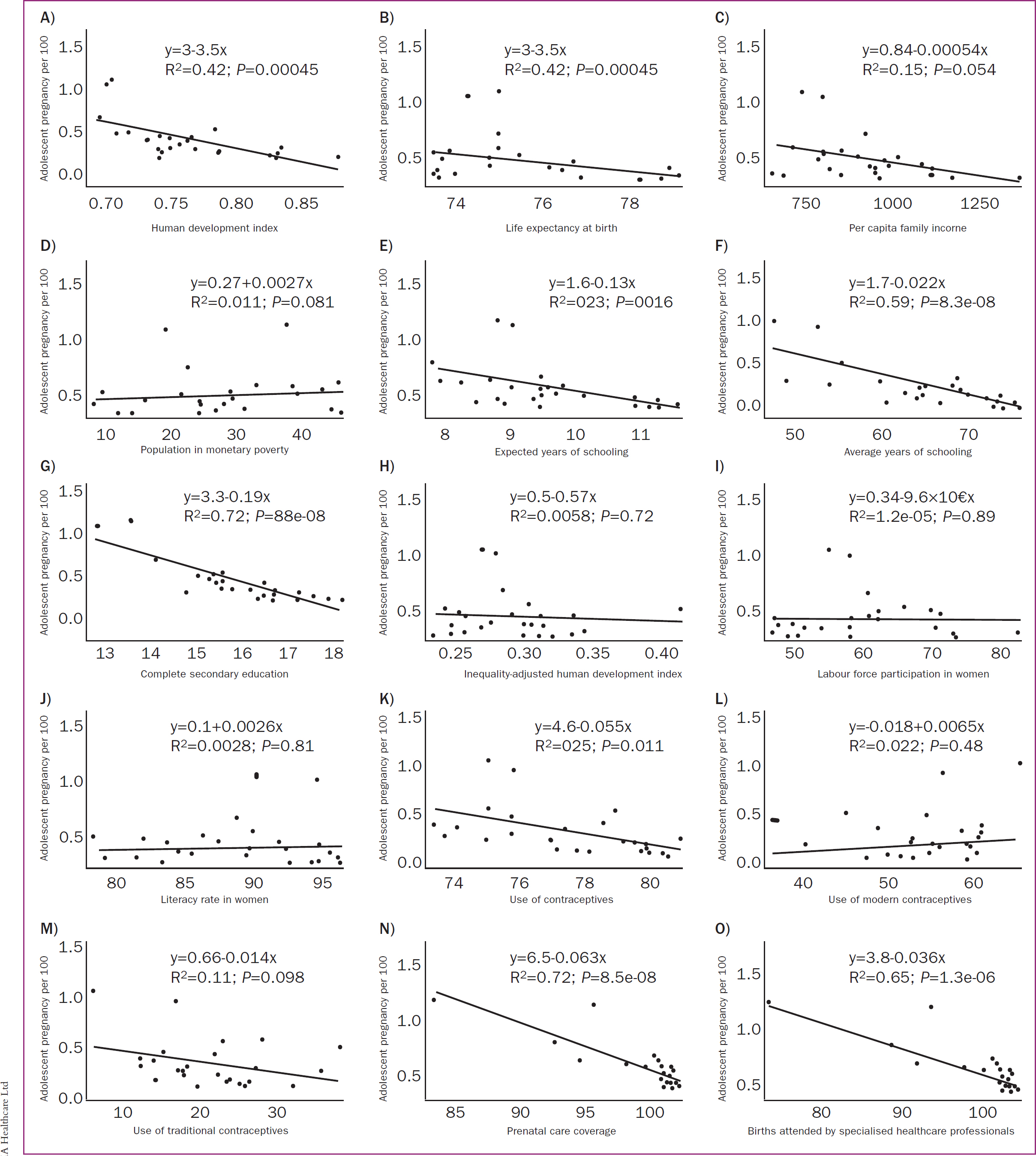

In simple linear regression analysis, several indicators showed significant associations with the early adolescent pregnancy rate, including complete secondary education (P<0.001), expected years of schooling (P=0.016), average years of schooling (P<0.001), contraceptive use (P=0.011), human development index (P<0.001), life expectancy at birth (P=0.027), prenatal care coverage (P<0.001) and births attended by specialised healthcare professionals (P<0.001). No statistically significant associations were found with the other indicators (Table 3; Figure 2).

| Variable | β | 95% confidence interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human development index | −3.50 | −4.61– −2.39 | <0.001 |

| Life expectancy at birth | −0.05 | −0.09– −0.01 | 0.027 |

| Per capita family income | <−0.01 | <−0.01–<0.01 | 0.054 |

| Population living in monetary poverty | <0.01 | −0.04–0.04 | 0.610 |

| Expected years of schooling | −0.13 | −0.24– −0.03 | 0.016 |

| Average years of schooling in those aged ≥25 years | −0.02 | −0.03– −0.01 | <0.001 |

| Complete secondary education in those aged ≥18 years | −0.19 | −0.24– −0.14 | <0.001 |

| Inequality-adjusted human development index | −0.57 | −3.81–2.67 | 0.718 |

| Labour force participation in women aged ≥15 years | <−0.01 | −0.01–0.01 | 0.987 |

| Literacy in women aged ≥15 years | <0.01 | −0.02–0.03 | 0.809 |

| Contraceptive use among women with a partner aged 15–49 years | −0.06 | −0.10– −0.01 | 0.011 |

| Modern contraceptives | 0.01 | −0.04–0.06 | 0.480 |

| Traditional contraceptives | −0.01 | −0.06–0.03 | 0.098 |

| Prenatal care coverage | −0.06 | −0.08– −0.05 | <0.001 |

| Births attended by specialised healthcare professionals | −0.04 | −0.05– −0.03 | <0.001 |

Discussion

The World Health Organization has identified adolescent pregnancy as a leading contributor to maternal and infant mortality rates that perpetuates the cycle of illness and poverty (Pan American Health Organization, 2022). It is considered a significant public health risk and a factor contributing to social exclusion and gender-based violence against women (United Nations Children's Fund, 2021). Despite the prevailing trend of delaying motherhood for professional, social and economic reasons, adolescent pregnancy persists as a consequence of inequalities in social determinants of health (Rosales-Silva and Irigoyen-Coria, 2013). The present study showed a significant association between adolescent pregnancy and several socioeconomic and reproductive health indicators in Peru.

Adolescent pregnancy rate by geographic region

Most research on adolescent pregnancy typically focuses on adolescents aged 15–19 years, excluding the particularly vulnerable group of those under 15 years old (Kassa et al, 2018; Karaçam et al, 2021; Lambonmung et al, 2022). In the present study, the adolescent pregnancy rate among Peruvian adolescents aged 10–14 years was 0.28 per 100 live births in 2017–2021. This is lower than rates reported in Brazil (0.65 per 100 live births in 2021) (Health Ministry, 2022) and Thailand (0.88 per 100 live births in the period 1992–2013) (Traisrisilp et al, 2015), but higher than China (0.02% in 2012–2019) (Xie et al, 2021) and Taiwan (0.03% in 2001–2010) (Weng et al, 2014).

Adolescent pregnancy is deeply influenced by social, cultural, educational and economic factors, which can place early adolescents in vulnerable situations (Neal et al, 2018). The highest adolescent pregnancy rate in Peru was in 2021, at 0.31 per 100 live births. This is not unexpected, as the United Nations Population Fund (2020) suggested that measures implemented to contain the COVID-19 pandemic may have hindered access to contraceptive methods and increased exposure to sexual violence and abuse in the family sphere.

The jungle regions of Peru, such as Ucayali and Loreto, exhibited the highest rates of adolescent pregnancy. A similar trend was reported in Hernández-Vásquez et al's (2021) previous study in Peru, which demonstrated a significant and positive association between adolescent pregnancy and the jungle region. This may be related to the fact that Loreto and Ucayali had the second and third lowest secondary school attendance rates in Peru, while Ucayali recorded the highest dropout rate in secondary education (United Nations Children's Fund, 2019).

Associations between pregnancy and indicators

There was an association between the human development index and the early adolescent pregnancy rate. These findings are similar to a previous study with adolescents aged 15–19 years in Peru, which reported this association at both district and provincial levels (Román-Lazarte et al, 2022). Research in Brazil reported that regions with higher human development indices had lower adolescent pregnancy rates, which could be considered a development marker (Vaz et al, 2016). Similarly, Martinez et al (2011) reported that adolescent pregnancy is more prevalent in environments characterised by limited development opportunities and social exclusion. Improving at least one dimension of human development, such as economic status through economic empowerment, may have the potential to reduce adolescent pregnancy (Nkhoma et al, 2020).

In regions with increased secondary education completion, years of schooling or expected years of schooling, there was a corresponding decrease in the pregnancy rate. Previous studies conducted in Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean support these results (Kliksberg, 2006; Martins et al, 2014; Kaphagawani and Kalipeni, 2017; Kassa et al, 2018). In Nepal, compulsory education was considered an effective strategy for delaying marriage, which in turn contributed to postponing pregnancy (Shrestha, 2002). In Nigeria, keeping adolescents in school was linked to delaying first childbirth (Fagbamigbe and Idemudia, 2016). Almeida and Aquino (2011) reported that women with a history of adolescent pregnancy often do not complete primary education.

A census in Peru reported that 30.5% of adolescent mothers did not receive formal education and there was a higher incidence of illiteracy with an increase in the adolescent maternity rate (National Institute of Statistics and Informatics, 2018). A significant consequence of the close connection between education and adolescent pregnancy is its contribution to perpetuating poverty, as adolescents who become pregnant are likely to drop out of school and not resume their studies later (Biney and Nyarko, 2017). Consequently, education is a fundamental socioeconomic factor in early adolescent pregnancy (Chung et al, 2018).

In regions with increased use of contraceptive methods among women aged 15–49 years old, there was a corresponding decrease in the adolescent pregnancy rate. This suggests that knowledge of pregnancy prevention methods could reduce the incidence of unplanned pregnancies (Ziyane and Ehlers, 2007). A prospective cohort study in Mexico reported that girls <15 years old were more likely not to use contraceptive methods before becoming pregnant because of a lack of sexual and reproductive education (Sámano et al, 2019). Similarly, a survey of 45000 people in five regions of Peru found that only 14% of young men and adolescent males always used condoms during sexual intercourse (Gutiérrez, 2022).

Comprehensive sexual education is a multidimensional solution for adolescents to acquire knowledge, develop skills and reflect on their attitudes and values, allowing them to make informed decisions about their sexual lives (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2015). However, unlike other countries in the region, Peruvian regulations framing implementation of comprehensive sexual education lack national legal status, being limited to a ministerial resolution in the Ministry of Education. This has resulted in deficient implementation of sexual education guidelines, reflected in limited teacher training and the absence of evaluation and monitoring systems to ensure quality comprehensive sexual education (Motta et al, 2017). A study of schools from three geographically and culturally diverse regions of Peru (Lima, Ucayali, and Ayacucho) found that coverage of sexual education was minimal; only 9% of students received instruction in each of the 18 topics that ensure a comprehensive approach to sexual education (Motta et al, 2017). The least addressed topics were contraception and unwanted pregnancy, values and interpersonal skills, and HIV/sexually transmitted infection prevention, with less than half of the students reporting learning about any of these topics (Motta et al, 2017).

In regions where there was an increase in prenatal care coverage or births attended by specialised health personnel, there was a corresponding reduction in the pregnancy rate. This highlights the importance of expanding insurance coverage and improving access to medical care in order to reduce the adolescent pregnancy rate. A study in the USA found that the availability of family planning clinics was associated with lower rates of adolescent pregnancy (Shoff and Yang, 2012). Similarly, Nearns (2009) reported that insured women aged 18–24 years old were three times more likely to use contraceptives than those without health insurance, suggesting that insurance coverage is important for accessing contraception (Nearns, 2009). However, it should be noted that the situation in the USA regarding health insurance cannot be generalised to contexts such as the jungle populations of Peru, where factors such as health infrastructure, geographic and cultural barriers and limited access to health services are more relevant determinants than the availability of insurance.

If adolescents' knowledge of reproductive health and hormonal contraceptives is inaccurate, they may not actively seek medical services (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2002). Moreover, it has been shown that economically disadvantaged adolescents are less likely to be insured than wealthier adolescents (Newacheck et al, 2004). Consequently, a comprehensive health insurance programme may have greater impact in reducing adolescent pregnancy among less wealthy populations (Miller et al, 2013).

Implications for practice

Monitoring was previously carried out across 109 health establishments in Peru (Ombudsman's Office, 2021). The main findings were that the following areas were lacking: information for pregnant girls and adolescents about sexual and reproductive health rights, knowledge of the technical guide on abortion, training of healthcare professionals and personnel fluency in the predominant language (Ombudsman's Office, 2021). It is crucial to develop and/or enhance public policies and programmes that improve access to sexual and reproductive health services, while ensuring these initiatives actively involve vulnerable populations in their design. This engagement helps ensure that policies are both accessible and relevant, especially in areas with high rates of teenage pregnancy. It is recommended that future qualitative research is conducted, as this is most suitable for exploring socially complex phenomena, such as the experiences of pregnant adolescents.

Strengths and limitations

One of the main strengths of this study is the quality of the birth certificate system, which demonstrates data integrity and consistency for most variables, particularly maternal age. A World Bank (2014) report showed that this information system covers approximately 96.7% of total birth records. However, this may mask underreporting in indigenous populations in the jungle and highland areas, because Peru's geographic challenges impact health service provision, including birth registration. Children born in health facilities are likely to receive birth certificates quickly, while those born elsewhere require extra steps for registration (Unicef, 2016).

To the best of the authors' knowledge, this study is one of the few quantitative investigations into the role of social determinants in adolescent sexual and reproductive health, and the first specifically focusing on early adolescents. These findings provide a robust foundation for further exploration of the role of social determinants of health and adolescent pregnancy in a more comprehensive manner.

However, there are limitations to consider. First, the design used may be susceptible to ecological bias, where observed correlations between groups do not necessarily extend to the individual. However, ecological studies support the hypothesis that the risk of adolescent pregnancy is not only restricted to individual characteristics but also to interactions with an individual's environment. Second, the indicators used were regional, and will not have captured local variations that may be relevant to understanding differences within a region. The studied indicators were not available at the local level.

The inequality-adjusted human development index does not represent a specific measurement of gender inequality but is a simple adaptation of the human development index to include the difference between men and women. Its interpretation should not be made independently of the human development index (United Nations Development Programme, 2018). This indicator was included as it provides the only available data indirectly related to gender inequality at the local level. However, it is important to exercise caution in interpreting this result because of the conceptual deficiencies associated with the human development index.

Despite these limitations, the findings offer a general overview of the issue and its links to socioeconomic factors, gender inequality and reproductive health indicators. This information is particularly relevant for policymakers, public health officials and researchers focused on adolescent health and education.

Conclusions

This study found that the rate of early adolescent pregnancy was higher in regions of Peru characterised by a lower human development index, lower completion of secondary education, reduced use of contraceptives and suboptimal use of healthcare services. This reinforces the notion that adolescent pregnancy is a multifaceted phenomenon linked to numerous economic, social, sexual and reproductive health factors. Its occurrence varies across geographic regions and social groups, necessitating comprehensive solutions that extend beyond healthcare interventions alone.

As a result of this complexity, strategies that enhance or optimise the diverse resources of regions and compensate for previous social disparities are needed. Effective public health policies should adopt a multidisciplinary approach to promote the wellbeing of this population, encouraging active participation from society and families to enhance education and access to reproductive health information among early adolescents.