Historically, continuous professional development for healthcare professionals has been delivered face-to-face (Ngenzi et al, 2021). However, in recent years, online learning has dramatically increased in availability (García-Morales et al, 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic greatly accelerated the move to online learning or blended education (Chick et al, 2020). It provided ‘a challenge and an opportunity to use and assess e-learning’ and to observe learners transitioning to a new method of learning (Bani Hani et al, 2021). Learners who were previously resistant to online learning needed to grapple with this transition, as were educators with low digital literacy. As noted by Bdair (2021), the COVID-19 ‘crisis created a new motivation to adapt to this valuable teaching strategy’.

‘Online learning refers to instruction that is delivered electronically through various multimedia and Internet platforms and applications’ (Maddison et al, 2017). It is usually broken down into two categories: ‘synchronous (instructor and students physically separated by distance but communicating in real time, as in video conferencing) and asynchronous (instructor and students whose communications are separated by both distance and time, as in web-based courses)’ (Roblyer et al, 2007).

In an Irish context, Callinan (2020) found that ‘dedicated time; quick technical and administrative support; computer training before completing an e-learning course and regular contact with the tutor in online course work’ all encouraged healthcare professionals to engage with online learning. As reported by Mukhtar et al (2020), the advantages of online learning for the learner include that it is learner centred and flexible, which are benefits for busy professionals dealing with ongoing staffing pressures. Online education also has significant benefits for healthcare organisations, namely accessibility, relevance, scalability and engagement (Tudor Car et al, 2018). Online education courses can be an economical option, with similar knowledge transfer to traditional face-to-face courses (Rudd, 2019).

Challenges with online learning include lack of interactivity and difficulty maintaining engagement (Goodwin et al, 2022) Factors affecting learner's perceived satisfaction include ‘learner computer anxiety, instructor attitude toward e-learning, e-learning course flexibility, e-learning course quality, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and diversity in assessments’ (Sun et al, 2008).

The Centre for Midwifery Education in Dublin provides education to midwives and nurses in the three Dublin maternity hospitals and the Greater Dublin Area in the Republic of Ireland. The education and training provided is mostly for continuous professional development. An educational technologist was recruited in 2019 and this marked a significant increase in online learning education provided by the centre.

Having previously provided predominantly classroom-based learning, when the COVID-19 pandemic began, the Centre for Midwifery Education temporarily moved solely to online learning to fulfil the learning needs of the nurses and midwives it served. Each programme was developed by a team consisting of an experienced educational technologist in partnership with a midwifery/nursing educator and a team of subject matter experts. According to the suitability of the topic, the decision to adopt an asynchronous approach rather than a ‘blended learning’ approach that used ‘a combination of digital and traditional learning methods’ (Tudor Car et al, 2018), was agreed upon by all members of the team. The online learning courses combined learning outcomes, video, images, text, voice recordings and quizzes, structured in a linear fashion in a learning management system. This system includes ‘a variety of software and systems used to manage, track, and deliver educational materials, as well as manage student records’ (Rosário and Dias, 2022).

The aim of this study was to evaluate six asynchronous (‘own time, own place’) online learning courses provided to midwives and nurses in the Republic of Ireland. The objectives were to capture participants' reactions to the online courses and assess the suitability of online learning to deliver continuous professional development.

Methods

A descriptive approach was used where participants' reactions to the courses were captured from post-programme evaluation questionnaires. The target group were nurses and midwives attending the following courses, chosen for their commonality, as the content was primarily theoretical:

Recruitment

The evaluation questionnaire was hosted on the Centre for Midwifery Education's online booking system. All midwives and nurses who enrolled in one of the six online courses were invited to participate in the research study, as a convenience sample. The inclusion criteria selected for midwives and nurses who had completed one of the courses offered by the Centre for Midwifery Education and were working in the Republic of Ireland. All Centre for Midwifery Education programmes are advertised on the online booking system and are open to healthcare professionals (mainly midwives and nurses) across the Republic of Ireland.

Data collection

Data were collected via programme evaluation questionnaires from January 2021 – January 2023. It is standard practice at the centre for all course participants to complete post-programme evaluations for the purposes of quality improvement. The questionnaire consisted of 12 questions (Table 1) and was developed by the research team. It was piloted with a small cohort of learners and minor edits were made in relation to formatting.

| Statement/question | Response format |

|---|---|

| This programme met the stated learning outcomes | Likert scale (agree strongly, agree, disagree, disagree atrongly, N/A) |

| The sessions were well presented | Likert scale |

| The content of the course was evidence based | Likert scale |

| I will apply the learning to my practice | Likert scale |

| I would recommend this programme/course/training to a colleague | Likert scale |

| The programme incorporated a variety of activities to facilitate engagement | Likert scale |

| As a result of national public health guidance, where feasible, education is being delivered online. What would your preference be if we were to continue to host this programme online? |

|

| When health restrictions are lifted, what would be your preferred mode of delivery for this programme? |

|

| Are there any benefits to online learning for you? | Yes/no |

| If yes, can you please name them? | Open ended text response |

| Are there any aspects of face-to-face teaching that you feel are missing from the online learning environment? | Open ended text response |

| What can we do to improve this programme (eg any suggestions for new interactive activities)? | Open ended text response |

The finalised questionnaire was presented to participants upon completion of the online course. The questionnaires consisted of a series of statements using a four-point Likert attitudinal scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’ (and including ‘not applicable’). These statements explored participants' satisfaction with the learning, their preferred type of learning and their response to online learning in general. Qualitative questions were also included at the end of the questionnaire. Learners had the option to skip questions.

The questionnaire was hosted on the Centre for Midwifery Education's online booking and certification system. It took 5–10 minutes to complete and was anonymous.

Data analysis

Surveys were analysed using descriptive statistics. Answers to open-ended questions were used to support quantitative findings. The Centre for Midwifery Education exracts these data from the online booking system in a fully anonymised, disaggregated format. For this reason, pseudonyms are not available for quotations.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted from the Research Ethics Committee in Coombe Hospital, Dublin, Ireland (reference: 9-2024). All information was held in confidentiality and anonymity was protected throughout the study. Only the researchers had access to the collected data, and IP addresses or names were not collected.

Results

A total of 1559 healthcare professionals accessed the six online learning courses between 19 January 2021 and 19 January 2023. Overall, 1413 questionnaires were undertaken, a total response rate of 90.6%.

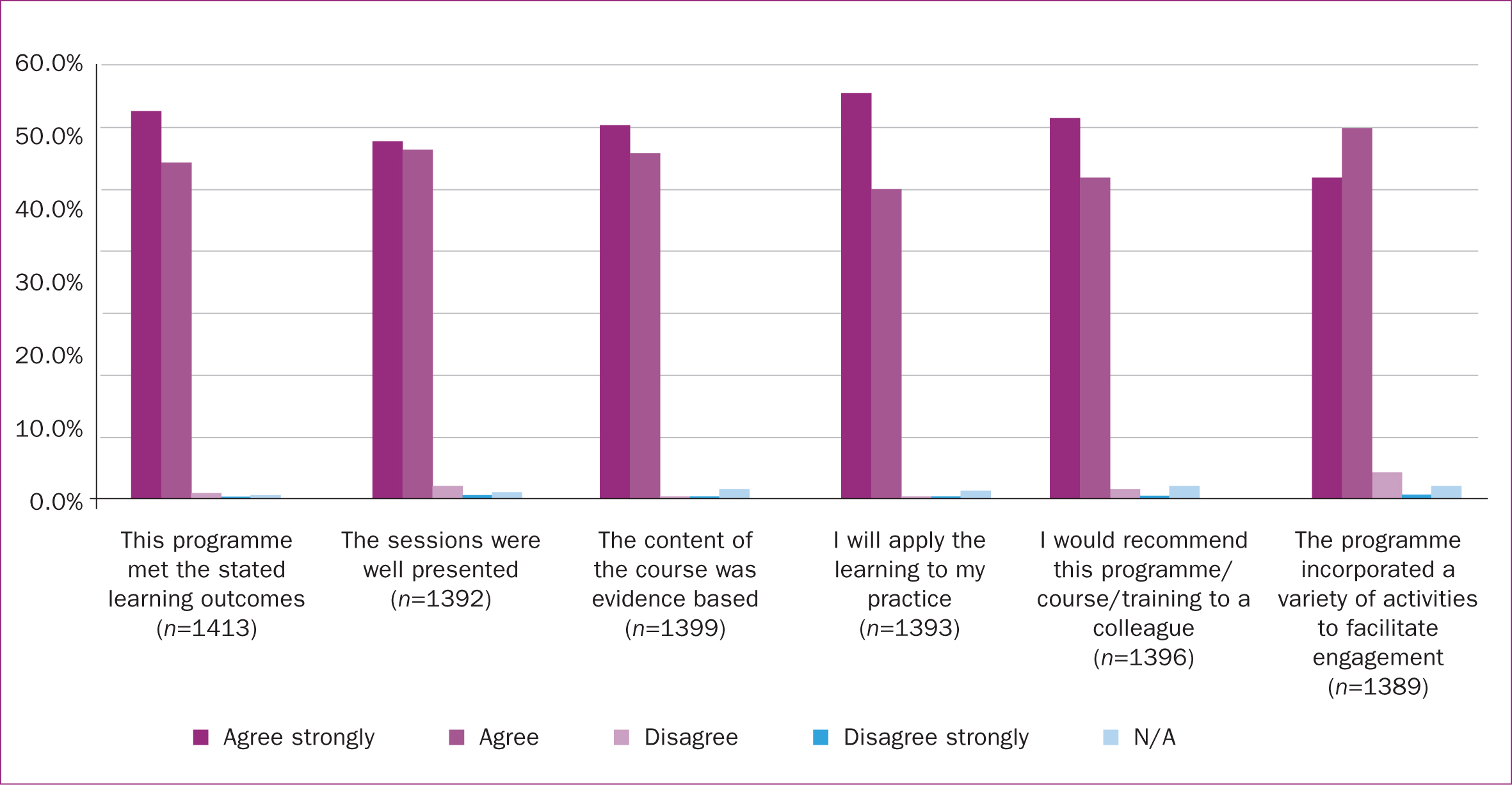

Initially, participants were asked a series of questions to evaluate the course they had just completed. A significant majority of those who attended reported feeling positively about their learning experience (Figure 1).

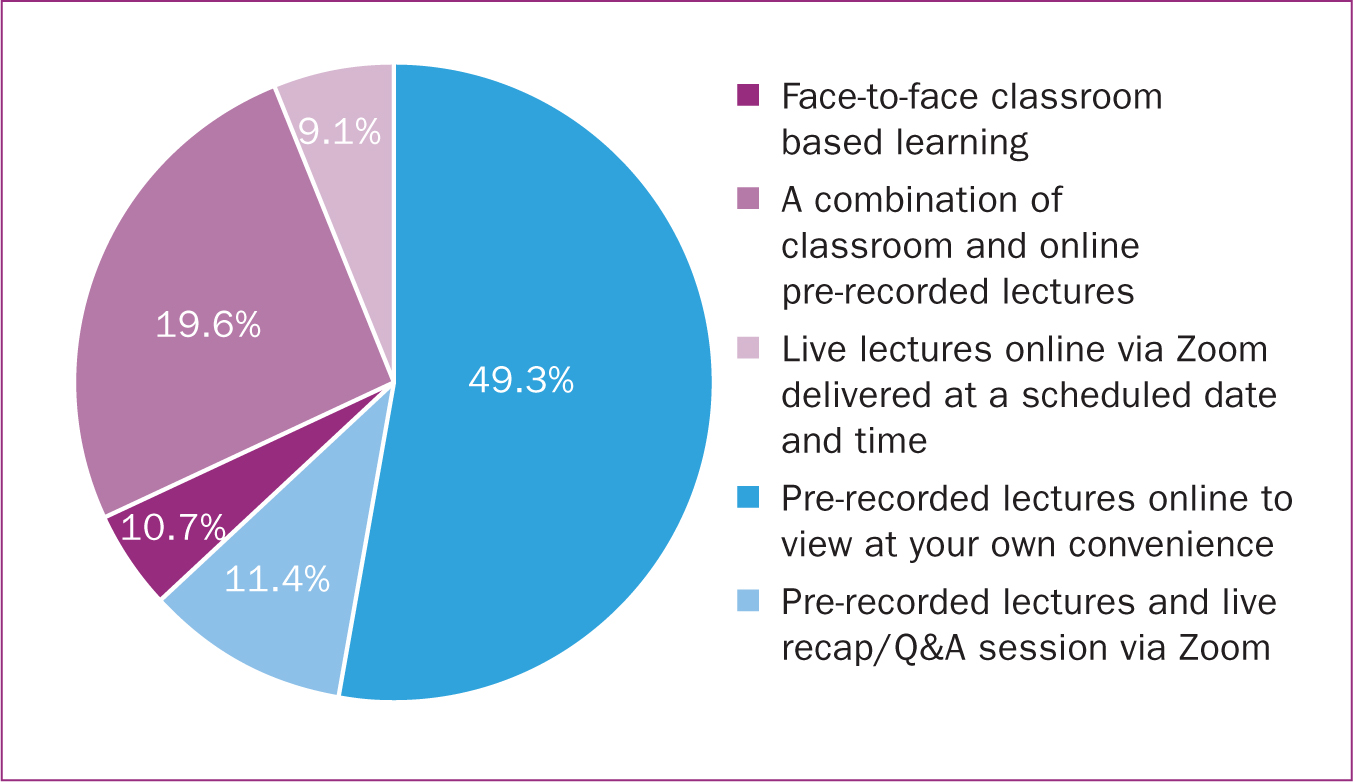

When asked for their preference if the centre were to continue to host the programme online, the majority (78.6% of 1386 participants) preferred pre-recorded lectures online (Figure 2). Almost half (49.% of 1381 participants) wanted pre-recorded lectures online as their overall preferred mode of delivery (Figure 3).

The majority (94.5%) of the 1318 participants who answered the question felt there were benefits to online learning. When asked what these benefits were (n=1086), 35.4% mentioned the ability to do the course in their own time.

‘Ability to complete at time convenient for me. Does not interfere with clinical commitments’.

‘Flexibility to do them at times that suit me’.

Almost a third (29.1%) mentioned convenience.

‘More convenient to do to work around personal schedule’.

‘More convenience with home life’.

One in 10 (9.6%) of the participants mentioned moving at their own pace.

‘Can go at my own pace, can stop and start, can go back on information where needed’.

‘No pressure in regards to time to complete. Can do at own pace’.

A small proportion (6.8%) mentioned the ability to refresh learning and skills.

‘To maintain safe and competent practice. Keeping up to date with required learning’.

‘Refreshes skills to apply in the clinical area’.

Some participants (5.7%) appreciated the lack of travel.

‘I dont live in Dublin where most courses are held; reduces commute’.

‘Save time in going to the lecture room’.

A similar number (5.2%) noted the benefits of a flexible location.

‘I can do online learning from home: the ward environment is usually too busy’.

‘Suits me to be able to complete from home, difficult to attend face to face study days with full time employment and family commitments’.

A few (3.9%) appreciated that the courses were available for review at any time.

‘You can go back to review the topics again if needed’.

‘It is great to be able to go back over the content at anytime’.

Some (2.5%) appreciated the time saved.

‘Less time consuming’.

Each of the other answer categories represented less than 2% of responses, were unintelligible or not related to online learning.

When asked about aspects of face-to-face teaching that were missing from the online learning environment, 63.4% of the 1083 participants who answered felt that nothing was missing, 18.4% said that interaction was missing, including discussion and knowledge sharing.

‘Interaction and more examples and case to case experience that can only be shared through face to face’.

‘Miss the human interaction from the classroom chat and sharing of experiences and ideas’.

More than one in 10 (13.7%) said that the ability to ask questions was missing.

‘Asking fellow colleagues and instructor questions’.

‘Feel it's easier to ask questions in face to face or clarify something’.

Each of the other answers represented below 2% of responses or were unintelligible.

Participants were also asked what could be done to improve the programme. Of the 867 participants who answered, 57.8% said that nothing needed to be done and 17.3% gave a generic positive response.

‘Keep it the way it is-I found it to be convenient and engaging at the same time’.

A small number (5.9%) of respondents requested content changes.

‘Add other case studies’.

‘More video presentations can be included’.

‘Add drawings please or illustrations’.

Similarly small numbers of participants requested that the courses be made more user-friendly (2.5%) or that it returned to face-to-face teaching (2.2%).

‘Simpler icons and user guide for it to be much easier to access esp. to senior staff not very good in online manuever’.

‘I was happy with the programme but would prefer lectures in a classroom’.

‘Preference is face to face as its more engaging’.

The other response categories represented less than 2% of responses each or were unintelligible.

Discussion

The results of this study showed that participants were extremely satisfied with the online learning courses provided by the Centre for Midwifery Education. Bani Hani et al (2021) found that learner satisfaction is positively linked to provider preparedness. In 2019, the Centre for Midwifery Education employed an educational technologist and moved to a more comprehensive learning management system, which improved the centre's ability to provide high-quality online education. This may have improved user experience and satisfaction.

Satisfaction rates in the present study may also have been influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic. Face-to-face learning was not permitted, and so learners had to undertake online learning courses as a necessity. This increased their engagement with technology and may have changed their attitude to online learning. As the data were collected from January 2021 to January 2023, study participants may have already overcome any fear of online learning and challenged some of their preconceptions.

Goodwin et al (2022) found that Irish undergraduate students were dissatisfied with asynchronous learning offered. Considering the high satisfaction rates in the present study, it is important to note that Centre for Midwifery Education programmes are overwhelmingly aimed at registered healthcare professionals undertaking continuous professional development, who may not require the same level of tuition and guidance as students. Renowned adult educator Malcolm Knowles posited that a learner matures and changes as they grow, becoming more self-directed and self-motivated. However, educators and designers need to deal with these learners differently, as they become largely motivated by ‘immediate relevance’ and ‘immediacy of application’ (Knowles, 1984). Both of these features are offered by online courses that equip nurses and midwives with knowledge and skills they can use in their role. Additionally, Centre for Midwifery Education learners were acquainted with asynchronous online learning before the COVID-19 pandemic, via national mandatory training courses, and prior use of an learning management system is also likely to result in increased satisfaction with online learning (Nikou and Maslov, 2023).

The success of online learning initiatives, is often partly attributed to thoughtful pre-planning and structured format of the courses (Teo et al, 2020). The planning and structuring phase may have helped the Centre for Midwifery Education to ensure the success of these online learning courses, as course providers were careful to choose topics that suited an asynchronous approach and engaged with managers and specialists to gain their support. Lower satisfaction rates with online learning were found in an Irish study that explored the use of online learning for palliative care education for healthcare professionals (Callinan, 2020). It was noted that the topic was ‘highly emotive and may be perceived as not particularly suited to e-learning’ (Callinan, 2020).

The quality of online course design is pivotal to learner experience and includes having clear learning outcomes, attention to accessibility and culturally inclusive media, all of which were considered in the design of these courses (Lewis, 2021). For other courses, that were deemed to require in-depth discussion, case review or skills, the centre supplemented asynchronous learning with Zoom classes (and face-to-face classes, after the pandemic).

The benefit of online learning mentioned most frequently was the ability to complete learning in one's own time. It is clear from the qualitative comments that learners in this study experienced barriers to education such as a busy schedule, childcare, family commitments, parking at work, travel on their day off, a busy working environment and limited staff. Doherty and O'Brien (2022) explored burnout in Irish midwifery and ‘insufficient time’ was highlighted as a source of frustration leading to burnout. Therefore, the opportunity to learn at a time that is convenient for learners is beneficial.

Asynchronous education can also reduce commute times and allow learners to use shorter periods of time and come back to the course later, which can be more convenient and less stressful for the learner. As noted by Tudor Car et al (2018), healthcare professionals lack protected time for training, which means that a unique approach should be adopted to address the particular barriers to learning for this group.

Implications for practice

The evidence of high rates of satisfaction with asynchronous online learning in this study may assist healthcare educators in the Republic of Ireland to advocate for online learning and encourage reluctant learners to give online learning a chance. Research suggests ‘increasing awareness about the usefulness and benefits of the e-learning system to increase its usability and popularity’ (Al-Fraihat et al, 2020). It may also serve to ease the apprehensions of staff who are hesitant to engage in online learning. As Lucas and Vicente (2023) noted, ‘how teachers perceive [online teaching and learning], specifically the benefits and challenges they associate with it, will determine their technology adoption and shape their educational practices’. It gives educators an example of what can be achieved in a healthcare education setting. The authors of this study hope to enthuse learners and educators by publishing this research and advertising the results in a poster in the learners' workplaces.

When respondents were asked how the courses could be improved, ‘nothing’ or generally positive feedback were the most common responses. The lack of suggestions for improvement reflects the high level of satisfaction with the courses. However, respondents noted that interaction and an ability to ask questions are missing from the asynchronous online education they received. This is supported by literature that notes that reduced engagement, interaction and feedback is a significant challenge with online learning (Bdair, 2021). This could also be addressed by complementing the courses with live group work or adding a forum. Training for educators on interactive strategies for asynchronous learning would also be required. Also, as noted by Paquette (2016), many educators are aware of benefits of collaboration and a learning community but require training on encouraging such. Further research may be taken by the Centre for Midwifery Education to add a forum (with an assigned and trained tutor) to one of the asynchronous online courses and explore the impact that has on the learner experience.

Conclusions

In recent years, many education courses for midwives and nurses have moved online. Post-pandemic, we have the time and experience to fully reflect on that change and we need to ensure that learners' needs are fully met by this change. It is timely that midwives' and nurses' educational needs and preferences are explored. The results of this study showed that participants were extremely satisfied with the asynchronous online learning provided. The ability to complete in one's own time, move at their own pace, refresh learning, reduce travel, complete from any location, review at any time and save time were highlighted as benefits. Areas for improvement were also highlighted, mainly a need for increased interaction and opportunities for enquiry from learners. The findings from this study will be used to inform the creation of future online learning programmes for midwives and nurses.